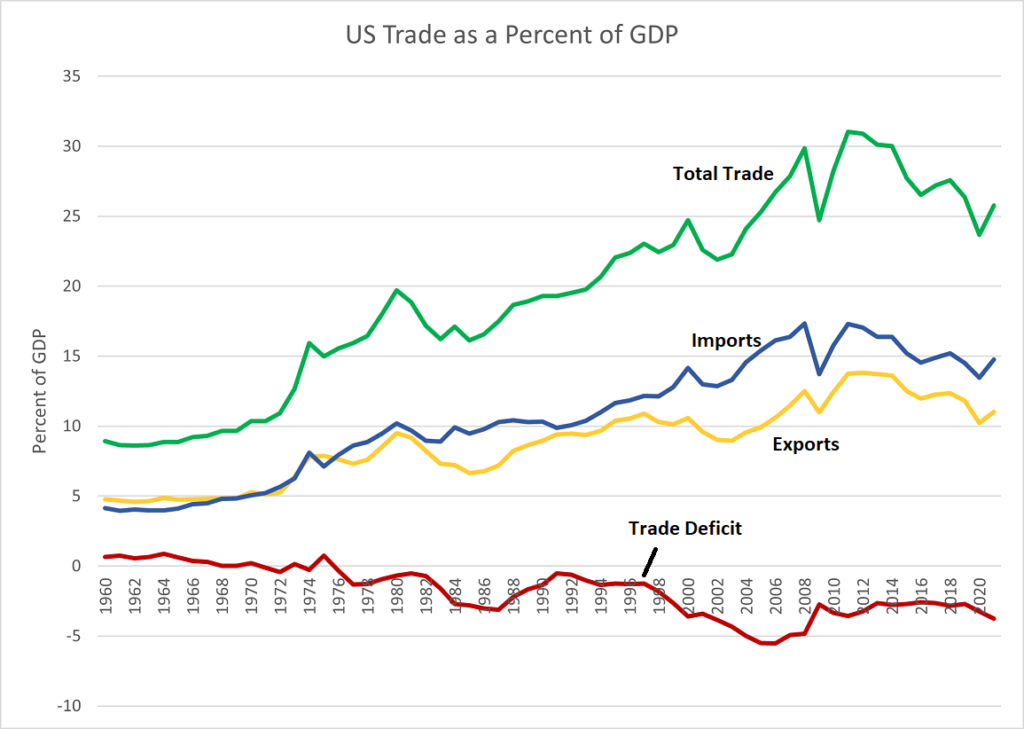

The chart below shows imports, exports, and the trade balance of the US as a percentage of GDP.

Figure 27: US Trade as a Percent of GDP. The trade deficit gets larger as it goes more negative. Data Source: BEA

US imports and exports totaled a combined $5.6 trillion in 2019, one quarter the size of the entire economy! While the US has the largest combined value of imports and exports in the world, on average most countries do even more trading compared to the size of their economies. The chart below shows trade as a percentage of GDP for the world, the US and China.

Figure 28: International Trade as a Percent of GDP Source: World Trade Organization, data from database: World Development Indicators. Note: trade includes both imports and exports. The World number is a weighted average of trade as a percent of GDP across countries.

Several things stand out. First is the high level of trade worldwide. In the case of the US, as we noted earlier, it is now around 25% of GDP, but for the world as a whole it is above 50% for imports and exports combined. Second, while the ratio of trade to GDP grew steadily until 2007, it has declined since then. In part this is due to economic conditions, the 2008 credit crisis caused a contraction in trade, but the decline continued after conditions improved. Finally, it is interesting to note the steep decline in trade as a percentage of GDP for China since 2004. China’s internal demand has increased substantially, so more of its total output (GDP) is being consumed within the country. India shows a similar trend. The US GDP is the largest in the world, and it is also the largest importer in the world in dollar terms, followed by China and Germany. The US ranks second after China in exports, with Germany again in third place.

World GDP has increased enormously, and since trade has risen as a percent of GDP, it has grown even faster, in a steep logarithmic curve. A real time interactive map of the giant cargo ships and tankers that ply the oceans looks like thousands of ants on the march[1]. Why has trade increased as a percent of GDP? The main factors are lower transport costs, lower tariffs negotiated in trade agreements, countries such as China opening up to trade, computerized logistics, increased demand for resources such as oil, and the freer movement of capital which makes it easier to manufacture where costs are lower and ship the goods.

The chart below shows the largest goods exports by product worldwide. Services exports have increased in recent years and are now nearly a third as large as trade in goods.

Figure 29: World Exports by Product Type. Data Source: UN Comtrade extracted through World Bank WITS interface.

Total world goods trade in 2019 was around $19 trillion, or almost the size of US GDP. Service trade came to around $6 trillion. Worldwide, agricultural product exports were around $1.8 trillion, or around 10% of the total. It is clear that world trade is dominated by manufactured products. As the chart shows, the large electrical and machinery category[2] has the highest global trade volume followed by fossil fuels, vehicles, and chemicals.

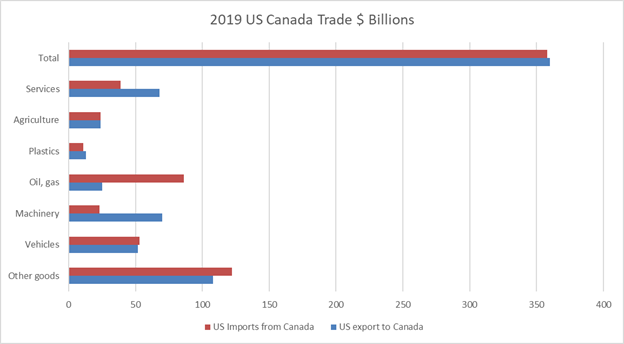

It is interesting to look at trade between countries. Here, for example, are the major items traded between the United States and Canada

Figure 30: 2019 US Canada Trade. Data Source: US Trade Representative

Trade between the US and Canada was almost balanced at $350 billion in 2019, and each of the major goods traded is found on both sides of the exports and imports ledger. The US exports as much in cars and car parts as it imports, both countries’ major exports to the other include machinery, fossil fuels, plastics, and agricultural products. It is almost as if the US and Canada are one large country from a trade perspective. That is no accident, the volume of trade between countries is highly influenced by proximity. The top three US trading partners in 2019 were Canada, Mexico, and China in that order. Shipping costs are lower when countries are close to each other, and tariffs and other trade barriers may be lower as well. This pattern is observed worldwide.

In looking at what gets traded between countries, detailed studies have shown that developed countries such as the US and Canada tend to trade similar types of products, often with a high level of technical sophistication. As trade barriers drop, fully developed countries tend to specialize in their bilateral trade: so, for example the US exports car parts to Canada where cars are assembled and then shipped back to the US. Trade between a developed country and a developing one also tends to be more complimentary than competitive, but in this case different types of products are traded, at least after trade barriers have been removed long enough for the dust to settle[3]. This is not particularly surprising if we recall the discussion of comparative advantage in the primer. In general, developing countries have a comparative advantage in labor and developed countries have an advantage in technology and capital intensity.

China is among the largest exporting and importing countries in the world. Now an upper middle-income country with a per capita GDP of over $12,000, China has come a long way on the path to development. We already looked at how it achieved its amazing growth, but here are a few of its notable trade statistics from 2019[4]:

- China’s largest trade partners in 2019 were the EU, the Asian countries (ASEAN), and the US in that order.

- In 2019, for the first time, China’s domestic owned private companies trade, at 42.7%, was higher than trade by foreign owned companies at 39.9%. State owned enterprises accounted for the rest. Foxconn is an example of a foreign company (it’s Taiwanese) with major investment in China[5].

- Electronics and machinery made up 58.4% of total exports. This included computers ($150 Billion), cell phones ($224 Billion), and integrated circuits ($102 Billion).

- Labor intensive industries including textiles and apparel made up 19.2% of exports.

- “Processing trade”, or assembling products made from largely foreign components, made up 25.2% of total trade.

- China’s trade is almost balanced, it had a net trade surplus of 0.7% of GDP in 2019.

Foreign companies have pumped huge amounts of capital into China to make use of its abundant lower-cost labor. Both foreign and domestically owned Chinese companies assemble products from imported components in what is called the “processing trade”, a high-volume low margin business. The box below details one company built on the processing trade and gives a feel for trade flows between developing and developed countries.

| Foxconn and Apple The Taiwanese company Foxconn, the largest private employer in China, operates huge self-contained factory “cities” which produce almost all Apple products including the iPhone, Amazon’s Kindle and Echo, Nintendo gaming systems, Nokia devices, Sony devices including PlayStations, Google Pixel devices, Xiaomi devices, every successor to Microsoft’s first Xbox console. In 2012, Foxconn estimated that its factories manufactured an estimated 40% of all consumer electronics sold worldwide. Some of the Foxconn factories employ hundreds of thousands of workers within self-contained walled “campuses”. To quote from a recent article in Foreign Affairs Magazine: At the gigantic Shenzhen Longhua “campus,” as the Foxconn managers like to call it, there are multistory factories, high-rise dormitories, warehouses, two hospitals, two libraries, a bookstore, a kindergarten, an educational institute (with the grandiose name “Foxconn University”), a post office, a fire department with two fire engines, an exclusive television network, banks, soccer fields, basketball courts, tennis courts, track and field, swimming pools, cyber theaters, shops, supermarkets, cafeterias, restaurants, guest houses, and even a wedding dress shop. Foxconn’s campus is the very image of a modern company town. The assembly lines run on a twenty-four‑hour basis, particularly when the production schedule is tight. The workplace and living spaces are compressed to facilitate high-speed, round-the-clock production. The dormitory warehouses a massive rural migrant labor force isolated from family relations. Whether single or married, each worker is assigned a bunk space for one person. In contrast to the corporate image of “a warm family with a loving heart,” Foxconn workers frequently experience isolation and loneliness—some of it seemingly deliberately created by managerial staff to prevent the formation of strong social bonds among workers. Managers, foremen, and line leaders prohibit conversation during work hours in the workshop. New workers are often reprimanded for working “too slowly” on the line, regardless of their efforts to keep up with the “standard work pace.” “Outside the lab,” according to an ominous saying of CEO Terry Gou, “there is no high tech, only implementation of discipline.”[6] This sounds like a modern version of the early English textile mills, but in this case the factories run 24 hours a day. While China officially has a 40-hour work week, Foxconn requires workers to work overtime especially in preparation for a holiday season or the release of a new iPhone version. Foxconn makes products for many big-name companies, but its tight relationship with Apple is particularly well known. Here is a comparison of the two companies: Company 2019 Revenue $Billion 2019 Profit (net income) $Billion Employees Revenue per employee Profit per employee Foxconn $178 $4 1,290,000 $137,984 $3,419 Apple $260 $55 154,000 $1,688,312 $357,143 Apple outsources almost all of its manufacturing, primarily to Foxconn, preferring to concentrate on design, engineering, managing, branding, and selling which, as the chart indicates, is much more profitable than manufacturing. While Foxconn operates most of its factories in China, it has about 25% of its capacity in other low wage countries. In 2017, to great fanfare, Foxconn announced plans to build a $10 billion electronics factory to build high-def TV screens in Wisconsin. The state’s then Governor had negotiated $3 billion in tax breaks and other subsidies. In 2020 Foxconn officially abandoned the plan[7]. The reasons are not hard to figure out: it is highly unlikely that US workers would accept the working conditions and starting pay of around $3 per hour that is endured by Foxconn’s young rural Chinese workforce. While TV screens cost more to transport than iPhones, it is likely the deal was driven more by public relations and risk hedging than by rationalizing business operations. None of this is to paint Foxconn or Apple or China as untypical, rather the reverse. If Apple didn’t have its products manufactured at the lowest possible cost while still maintaining quality, it would be less profitable. If Foxconn didn’t seek out the lowest cost workforce and highest productivity while still maintaining quality, it could lose contracts. Given the demands of the free market, it is only through political means such as unions or government that workers within a political jurisdiction can set the rules under which companies operate. Developing countries meanwhile strive to attract foreign capital to drive up productivity and hence wages in the long run. Consumers of electronics all over the world benefit from low-cost electronics. Closing the door to imported electronics in the US would be next to impossible in the short run (Apple’s experience in Texas is telling[8]) and would cause the costs of these products to skyrocket. Higher prices are the same as lower pay, so the vast majority of Americans would end up with effective pay cuts in exchange for the factory jobs created. As we noted in the primer, trade between two countries is almost always beneficial to both regardless of the differential in average productivity and hence wages between them. It is the equivalence of lower prices and higher pay that often obfuscates this fact, along with the pain of employment adjustments. We’ll look at data on the “welfare” effects of trade a bit later. |

A contrast to China with its huge (but diminishing) supply of labor is Germany, a country on the productivity edge. Some German trade highlights[9]:

- Germany has one of the highest trade surpluses in the world at 7.6% of GDP in 2019 compared to China’s 0.7% surplus and the United States’ 2.3% deficit.

- Germany’s largest trade partners are the EU, the US, and China in that order.

- Germany’s largest exports include motor vehicles and parts ($205 Billion in 2019) and medical products including pharmaceuticals and medical instruments ($101 Billion) which together account for about 20% of total German exports. Textiles account for a tiny 0.07 percent of exports.

While Germany makes a lot of cars domestically for export, German companies, like most other car companies, build their cars using parts from widely distributed suppliers and often assemble them closer to where they are sold. Cars, unlike electronics, are heavy and there are tax advantages in assembling cars where they are sold. The box below focuses on foreign automobile manufacture in the United States.

| Made in America – Cars Unlike the case for electronics, even “foreign” cars such as Honda or Toyota, sold in the United States are often assembled here and contain parts from suppliers all over the world. An amusing 2015 article in Consumer Reports notes[10]: The U.S. saw an increase in automotive employment in the 1990s and early 2000s. German, Japanese, and South Korean automakers covered the American South with hulking final-assembly and supplier plants and tens of thousands of nonunion jobs that paid just well enough to fend off the United Auto Workers. The idea: Build ’em where you sell ’em. In an ironic turnabout from the years when naysayers decried made-in-Asia cars as little more than tin boxes built with cheap labor, the U.S. has become the low-cost labor source of choice for foreign brands. Korean automakers Hyundai and Kia jumped into the fray; even German luxury brands had little problem expanding outside home. In some cases, the assembled cars from foreign owned factories in the United States are exported. The Consumer Reports article notes that in 2014 BMW exported 70% of the output of its assembly plant in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Cars made by US automakers contain a lot of components made elsewhere, so the “Total Domestic Content” shown on new car window stickers is never 100%. In fact, because the large US automakers had assembly plants in Canada, just north of Detroit, back in 1994 when the American Automobile Labeling Act was passed, the act includes both US and Canadian content in the “domestic” tally. This explains the brisk two-way trade in vehicles and parts between the US and Canada we noted earlier. While the profits of foreign owned car operations in the US “belong” to the parent company, much of it is reinvested here. We benefit from the huge capital investment in plants and equipment as well as the employment and payroll supported. As of 2019 Japanese car companies had invested $51 billion in US plants that created 94,000 manufacturing jobs, and several times that number of supplier jobs. The difference in the employment picture between electronics and car manufacture comes down simply to cost minimization. For cars, the transportation costs of a finished vehicle are more than the labor cost savings from assembling the vehicle in a lower wage country such as China, so it is less expensive to assemble the car here. The reverse is true for lightweight electronics products. Many of the lighter components used in automobile assembly do in fact come from further away because their transportation cost is low. More recently Mexico, being close to the United States, has become a hub for automobile assembly. |

These two examples show that, not surprisingly, stuff is made where the total cost of producing it for its intended market is lowest when all costs are considered. In the case of Apple, the company decided to outsource, while in the US automobile case foreign companies invested in manufacturing plants here as well as buying from local suppliers. The calculation of how to maximize profit is far from simple since it involves decisions about investing versus outsourcing, labor costs, transportation costs, tariffs, geographic sales prediction, supply chain organization, taxes, local subsidies, and risk evaluation. And when components are assembled, the analysis has to be done for each component as well as the point of final assembly. The comparative ease with which capital flows around the world now, and the use of software to help with planning and tracking has encouraged the development of complex supply chains regardless of where a company is headquartered. Companies source services in much the same way. US companies often locate much of their engineering and information technology staff in countries such as India to take advantage of lower pay rates.

Faster, cheaper, and more predictable delivery of goods worldwide, software that can predict when components and materials will be required, and suppliers who can rapidly produce components on demand has led businesses to reduce stockpiling of parts. This “just in time” management style reduces the cost of warehousing and reduces waste and allows for more flexibility in product changes.

With post-covid hindsight, one can see how these complex supply chains and “just in time” management style can lead to problems when anything goes wrong. Pandemics and wars being examples of what can go wrong. In a remarkably prescient 2014 article on US Manufacturing[11] the authors, Baily and Bosworth note:

… a strong domestic manufacturing sector offers a degree of protection from international economic and political disruptions. This is most obvious in the provision of national security, where the risk of a weak manufacturing capability is clear. Overreliance on imports and substantial manufacturing trade deficits increase Americans’ vulnerability to everything from exchange rate fluctuations to trade embargoes to supply disruptions from natural disasters.

That said, globalization and complex supply chains are here to stay, although developing countries’ lower cost labor is far from the only determinant of where goods and services are produced. A recent article notes:

Yet counter to popular perceptions, today only 18 percent of goods trade is based on labor-cost arbitrage (defined as exports from countries whose GDP per capita is one-fifth or less than that of the importing country). In other words, over 80 percent of today’s global goods trade is not from a low-wage country to a high-wage country. Considerations other than low wages factor into company decisions about where to base production, such as access to skilled labor or natural resources, proximity to consumers, and the quality of infrastructure[12].

Both of these articles note the importance of a skilled, educated workforce and good infrastructure as being factors in a country’s competitiveness.

China has grown its GDP per capita rapidly and is now classified as an “upper middle income” country. Leveraging trade was one important factor in this growth, but while China still manufactures nearly half of the world’s clothing, that sector accounted for only 4% of China’s exports by value in 2022, down from 18% in 1994. Meanwhile other countries such as Bangladesh and Myanmar with lower GDP per capita do far more of their trade in clothing. The chart below shows the relationship between the fraction of exports to the US that are clothing and 2019 GDP per capita for some Asian countries.

Table 6: Fraction of exports to the US that were clothes in 2019. These percentages are similar to each country’s world exports. Myanmar also exports some oil, so the percentage of its remaining exports in clothes would be higher. Data Source: World Bank WITS interface to UN Comtrade data.

| Korea, Rep. | China | Bangladesh | Myanmar | |

| GDP Per Capita 2019 | $ 31,902 | $ 10,143 | $ 2,122 | $ 1,295 |

| Percent of exports to US that are clothing 2019 | 0% | 6% | 86% | 33% |

Before we leave this section on trade flows, let’s look at the international transactions of the United States as reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis in its summary of the national accounts.

Table 7: International Trade Transactions of the United States, 2019

| Item | Exports $ Billions | % of Exports | Imports $ Billions | % of Imports | Net $ Billions |

| Total trade and foreign income | $3,812 | 100% | $4,285 | 100% | ($472) |

| Goods | $1,652 | 43% | $2,514 | 59% | ($862) |

| General merchandise | $1,632 | 43% | $2,502 | 58% | ($869) |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | $131 | 3% | $152 | 4% | ($21) |

| Industrial supplies and materials | $526 | 14% | $526 | 12% | $1 |

| Capital goods except automotive | $548 | 14% | $679 | 16% | ($131) |

| Automotive vehicles, parts, and engines | $163 | 4% | $376 | 9% | ($213) |

| Consumer goods except food and automotive | $205 | 5% | $656 | 15% | ($451) |

| Other general merchandise | $59 | 2% | $114 | 3% | ($55) |

| Non-Monetary gold | $19 | 1% | $12 | 0% | $7 |

| Services | $876 | 23% | $591 | 14% | $285 |

| Maintenance and repair services n.i.e. | $28 | 1% | $9 | 0% | $19 |

| Transport | $91 | 2% | $113 | 3% | ($22) |

| Travel (mostly tourist spending) | $199 | 5% | $133 | 3% | $66 |

| Construction | $3 | 0% | $1 | 0% | $2 |

| Insurance services | $19 | 0% | $52 | 1% | ($33) |

| Financial services | $136 | 4% | $41 | 1% | $95 |

| Charges for use of intellectual property n.i.e. | $116 | 3% | $42 | 1% | $74 |

| Telecommunications, computer, and information services | $55 | 1% | $43 | 1% | $12 |

| Other business services | $186 | 5% | $113 | 3% | $73 |

| Personal, cultural, and recreational services | $22 | 1% | $20 | 0% | $2 |

| Government goods and services n.i.e. | $22 | 1% | $24 | 1% | ($2) |

| Primary income receipts | $1,125 | 30% | $893 | 21% | $232 |

| Investment income | $1,118 | 29% | $874 | 20% | $244 |

| Direct investment income | $569 | 15% | $233 | 5% | $336 |

| Portfolio investment income | $424 | 11% | $507 | 12% | ($82) |

| Other investment income | $123 | 3% | $134 | 3% | ($11) |

| Compensation of employees | $7 | 0% | $19 | 0% | ($12) |

| Secondary income (current transfer) receipts | $159 | 4% | $287 | 7% | ($128) |

Table Notes: International Transaction of the US. This shows a net trade deficit of $472 billion. “Exports” is money earned by trade or investment from overseas, while “Imports” are amounts paid for imported items or money paid on investments by foreigners. Travel “export” mostly refers to tourist dollars spent here by foreign visitors, and imports refers to money spent by US tourists abroad. Secondary income includes remittances sent overseas by people working here (e.g. immigrants).

Source: BEA Table 1.2. U.S. International Transactions, Expanded Detail for 2019

From this table we can see that the US ran a substantial goods trade deficit, mostly for consumer goods, but ran a surplus in services. The US had a net positive income from overseas investments which helped reduce the trade deficit. Still the overall “current account” deficit (net trade plus net foreign income) was $472 billion.

The deficit in trade in goods and services has to be balanced somehow, either as debt or by selling an asset. The BEA also publishes a balance sheet for the “financial account” which records these transactions. Here are the financial transactions for 2019 at the national level.

Table 8: International Financial Transactions of the United States, 2019. Source: BEA Table 1.2. U.S. International Transactions, Expanded Detail for 2019

| Item | US Bought $ Billions | % of Assets Bought | US Sold $ Billions | % of Assets Sold | Net $ Billions |

| Net U.S. acquisition of financial assets excluding financial derivatives (net increase in assets / financial outflow (+)) | $317 | 100% | $756 | 100% | ($439) |

| Direct investment assets | $122 | 39% | $302 | 40% | ($180) |

| Equity | $157 | 49% | $262 | 35% | ($106) |

| Debt instruments | -$34 | -11% | $40 | 5% | ($74) |

| Portfolio investment assets | -$13 | -4% | $177 | 23% | ($191) |

| Equity and investment fund shares | -$163 | -52% | -$244 | -32% | $81 |

| Debt securities | $150 | 47% | $421 | 56% | ($271) |

| Short term | $136 | 43% | -$33 | -4% | $169 |

| Long term | $14 | 5% | $454 | 60% | ($440) |

| Other investment assets | $204 | 64% | $276 | 37% | ($73) |

| Other equity | $1 | 0% | $0 | 0% | $1 |

| Currency and deposits | $132 | 42% | $204 | 27% | ($72) |

| Loans | $69 | 22% | $62 | 8% | $7 |

| Trade credit and advances | $1 | 0% | $10 | 1% | ($9) |

| Financial derivatives other than reserves, net transactions | ($42) | ||||

| Total Financial Transactions listed | ($481) |

The financial accounts balance at $481 billion is pretty close to the trade balance of negative $472 billion.In other words, the US sold stocks, government and corporate bonds, US companies and new investments such as factories to balance the trade deficit. The difference between the trade (aka current account) balance and the financial account balance is explained by a few small items left out of the table (there is a small “capital account” also), and a statistical “error” caused by the difficulty of accounting for every last transaction. Without these offsetting sales of assets, the US, or any country, could not sustain a trade deficit. In the absence of such sales, the value of the US dollar would fall, making imports more expensive and exports cheaper, until trade again balanced.

Let’s look in more detail at the US trade deficit. The US has a somewhat unique position in the world due to the size of its economy and the status of the dollar as the premier reserve currency, but much of what applies to the US also applies to other large economies.

[1] There are many vessel trackers. See for example https://www.vesselfinder.com/. On the left you can choose the types of vessels shown. A “mega” cargo ship can haul as much freight as 3,800 trucks and 50 trains (https://shippingwatch.com/Ports/article11989745.ece). Ships account for over 80% of international shipping. There are over 50,000 large cargo carrying ships. For a great visualization see https://www.shipmap.org/

[2] This chart is aggregated using the Harmonized System 2017 coding, Electrical and machinery (Section 16) is very large, including everything from cell phones to nuclear reactors.

[3] Edwards, Lawrence, and Robert Z. Lawrence. 2013. Rising Tide, Is Growth in Emerging Economies Good for the United States? Peterson Institute for International Economics. See Table 4.1

[4] Review of China’s Foreign Trade in 2019, China Customs, http://english.customs.gov.cn/Statics/f63ad14e-b1ac-453f-941b-429be1724e80.html and data extracts from UN Comtrade through WITS

[5] The world recognizes Taiwan as part of China, but from an economic point of view it acts independently.

[6] Chan, Jenny. 2020. “Foxconn’s Rise and Labor’s Fall in Global China.” American Affairs Journal. November 20, 2020. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2020/11/foxconns-rise-and-labors-fall-in-global-china/.

[7] Isidore, Chris, and CNN Business. 2021. “Foxconn’s Giant Factory in Wisconsin Sounded Too Good to Be True. Turns out It Was.” CNN, April 22, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/22/tech/foxconn-wisconsin-factory-scaled-down/index.html. Also see Nusca, Andrew. n.d. “Apple Wants to Make Products in U.S., but That’s Not so Easy.” CNET. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.cnet.com/tech/tech-industry/apple-wants-to-make-products-in-u-s-but-thats-not-so-easy/.

[8] Nicas, Jack. 2019. “A Tiny Screw Shows Why iPhones Won’t Be ‘Assembled in U.S.A.’” The New York Times, January 28, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/28/technology/iphones-apple-china-made.html.

[9] UN Comtrade accessed through World Bank WITS

[10] “What Makes a Car ‘American’? – Consumer Reports.” n.d. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2015/05/what-makes-a-car-american-made-in-the-usa/index.htm.

[11] Baily, Martin Neil, and Barry P. Bosworth. 2014. “US Manufacturing: Understanding Its Past and Its Potential Future.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 28 (1): 3–26.

[12] Lund, Susan, James Manyika, Jonathan Woetzel, Jacques Bughin, Mekala Krishnan, Jeongmin Seong, and Mac Muir. 2019. “Globalization in Transition: The Future of Trade and Value Chains.” McKinsey & Company. January 16, 2019. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/globalization-in-transition-the-future-of-trade-and-value-chains. Note that China has less than one fifth the GDP per capita of the US, so trade between the pair would be included in the labor cost arbitrage grouping.