Income can be entirely consumed or part of it can be saved. If one saves over a period of time, one accumulates wealth. Economists like to say that income is a flow, and wealth is a stock, by which they mean an accumulation. As individuals we build wealth by saving and investing those savings. Countries also accumulate wealth by investing in, for example, highways or education. Companies too, can accumulate wealth, even though that wealth ultimately belongs to their shareholders.

In addition to the usual types of wealth such as stocks and bonds and mansions, there are other forms of wealth that are quite important and should be kept in mind. Wealth can include[1]:

- Financial Wealth: This is the most common and easily measurable form of wealth. It includes money, stocks, savings accounts, and other financial assets.

- Physical Wealth: Physical wealth comprises tangible assets such as real estate, land, buildings, vehicles, and valuable possessions like art, jewelry, and collectibles.

- Human Capital: Human capital represents the knowledge, skills, education, and expertise possessed by individuals. It can be a significant source of wealth, as people with higher levels of education and skills tend to have better earning potential and career opportunities.

- Social Capital: Personal social capital relates to the value derived from social networks, relationships, and connections. It can provide opportunities, support, and access to resources that contribute to an individual’s or organization’s wealth. At the national level social capital can include factors such as trust, social cohesion, and the effectiveness of social and political institutions.

- Intellectual Property: Intellectual property, such as patents, copyrights, and trademarks, can be a valuable source of wealth. These assets grant exclusive rights to ideas, inventions, or creative works, allowing their owners to monetize them.

- Natural Resources: In some cases, wealth is tied to the possession of natural resources like oil, minerals, forests, and agricultural land. The exploitation and management of these resources can generate substantial wealth for individuals and nations.

- Health and Well-being: Good health and well-being are often considered a form of wealth. They enable individuals to enjoy a higher quality of life and pursue opportunities for personal and financial growth.

- Time: Time can be seen as a form of wealth. Having control over one’s time, such as through flexible work arrangements or retirement, can be highly valuable.

With the exception of personal social capital and time, all these types of wealth pertain to both individuals and countries as a whole. Estimates of household and country wealth usually only include the net market value of financial and tangible assets, and intellectual property. It is also important to remember that a country’s wealth includes public investment or “common wealth”, in such things as infrastructure and an educated workforce which are key drivers of productivity and hence income increases.

Current Wealth Distribution

As with income, there are large differences in mean and median wealth between countries as well as a highly skewed wealth distribution within countries and indeed the world as a whole.

Between Countries

As with income, there are large differences in total wealth per person between countries, but the distribution of wealth within countries and regions is pretty similar around the world as shown by the table and chart below.

Figure 51: Mean and Median household wealth by region in 2021 US dollars. The Gini coefficient (row of numbers over bars) indicates a level of inequality: 100% is totally concentrated, 0% is totally equal. The blue area shows the relative population of each region. Date Source: “Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook 2022”, table 3-1, as aggregated in the Wikipedia article https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_wealth_per_adult#cite_note-CS2022-1-1r.WW127

The chart shows the huge differences in mean (i.e. average) wealth between regions. The faded blue background shows the population of each region. In each bar the difference between the median and mean wealth indicates the highly skewed nature of the wealth distribution within the population of that region. Mean wealth (mean is another word for average) is total wealth divided by the number of households: it is the wealth every household would have if wealth were evenly distributed. Median wealth shows the midpoint of actual wealth distribution: half of all households have more than this level of wealth and half have less. If the household wealth of China were evenly distributed, the average Chinese household would have as much wealth as the median US household.

The Gini coefficient (row of numbers over the bars) indicates the level of inequality within each region: 100% means one household has all the wealth, 0% is totally equal.

The main purpose of this chart was to show that there are vast differences in average and median household wealth between countries, but even here we see the skewed distribution of wealth within regions and countries.

Between Households

Household wealth distribution for the world as a whole is even more skewed than income distribution.

Figure 52: Global Income and Wealth Inequality. Source: “The World Inequality Report 2022.” October 20, 2021. https://wir2022.wid.world/chapter-2/. While economists differ in what should be precisely included in wealth, the data sources largely agree in terms of distribution. WW177

This chart shows the global share of income and wealth distribution among households. The top 10% (which includes the top 1%) has 52% of income globally but owns 76% of the world’s wealth. Meanwhile the bottom 50% has 2% of global wealth and the middle, between 50% and 90%, has 22%.

As of 2019 the US ratios for wealth were almost exactly the same[2]:

- The Top 10% owns 76% of wealth (12.9 million families)

- The Middle 40% owns 22% (51.4 million families)

- The Bottom 50% owns 1% (64.3 million families of which 13.4million had negative net worth)

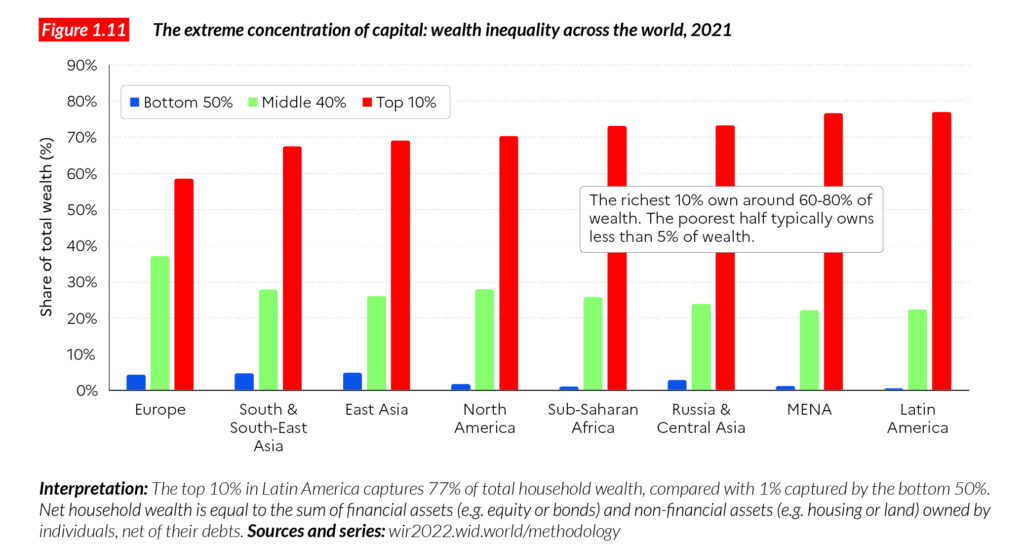

This distribution of wealth between households is pretty similar across world regions as shown in the chart below. Europe has a slightly bigger percentage of wealth held by middle wealth households, Latin America and MENA (Middle East and North Africa) somewhat less.

Figure 53: Source: “The World Inequality Report 2022.” October 20, 2021. https://wir2022.wid.world/chapter-2/. WW178

Given this uniform concentration of wealth at the top 10% level across countries and regions, one is tempted to wonder if this kind of ratio has persisted over time in relatively free market economies.

Wealth Distribution Over Time

The answer to the last question we asked is yes. Wealth inequality is more the norm than the exception and has persisted over history. Historians Walter Schiedel and Steven Friesen in their article “The Size of the Economy and the Distribution of Income in the Roman Empire” estimate that the top 1% in Rome controlled 16 percent of the wealth[3], although that is admittedly less than half of what America’s top 1 percent control now.

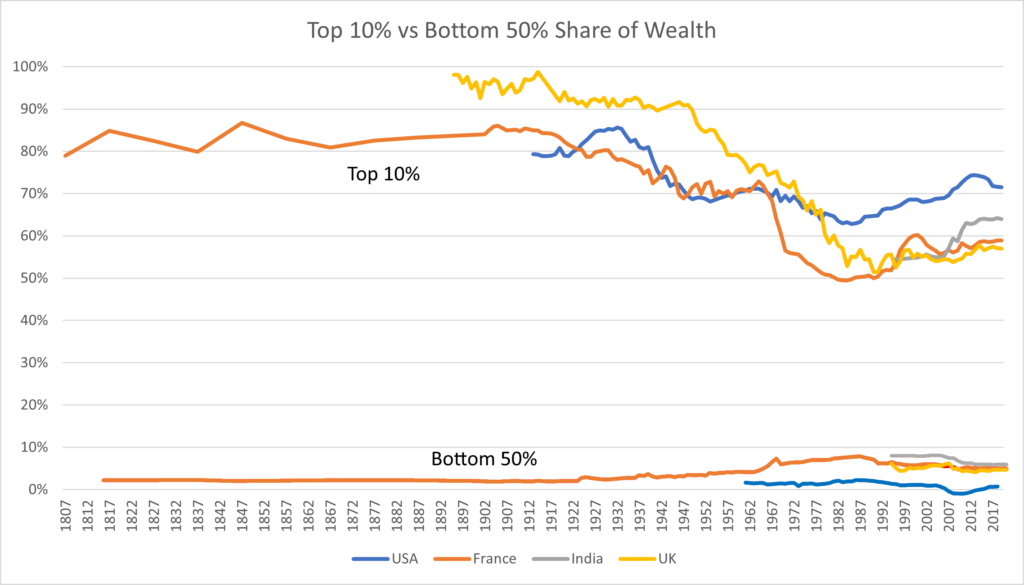

More recently Piketty, Saez, and Zucman and others have undertaken the enormous effort of collecting such historical information on income and wealth as can be found and making it as consistent over time as possible, as well as reconciling the data with national accounts. Here is a chart of the top 10% share of wealth from the World Inequality Database.

Figure 54: Top 10% and Bottom 50% Share of Wealth, Selected Countries. Data Source: World Inequality Database https://wid.world/. WW179

France has been collecting usable wealth data since the early 1800’s and the top 10% consistently owned over 80% of it. Consistent with the earlier chart, the bottom 50% has a tiny fraction of the wealth, with the “middle” from fifty percent to ninety percent owning the remaining roughly one quarter, mostly in the form of houses.

Thomas Piketty in his amazing, entertaining, and highly readable book “Capital in the 21st Century”, notes that 90% of French national wealth was inherited in 1910 falling to a low of 45% in 1970 but was back up to 72% when he published his book in 2014. Wealth was even more concentrated in Britain at the end of the 1800’s with large fortunes kept intact through “primogeniture”, or inheritance by the first male heir, and social norms. In the US, too, wealth was highly concentrated. In all three countries, as well as others, the concentration of wealth declined after the first World War and then more rapidly after the second World War, but has started to increase again since the 1980’s. There are a number reasons for the declines in wealth concentration before the 1980’s, they include the increased economic growth rate after the wars which tends to dilute existing fortunes, public sentiment which turned against concentrated wealth and resulted in legislation and tax structures that sought to reduce predatory practices (think antitrust in the US) and reduce the size of fortunes over time (think high marginal tax rates and estate taxes). More recently productivity growth rates have fallen, as we’ve seen, and at least in the US, effective marginal tax rates have fallen, especially on capital income. Both factors would tend to increase wealth concentration, as would the already noted unequal growth of incomes. The last few decades have also seen notable increases in the value of housing and equities.

The concentration of wealth in the upper 10% is not all a story of truly huge fortunes. While the top 1% own 38% of wealth, another 38% is owned by the richest 90-99 percent with a net worth that goes up with age, as is to be expected. The median net worth of the top 10% of US families was $2.6 million in 2019 according to the FED’s survey of consumer finances, but that includes the top 1%.

The top fortunes in the world are a mix of “new” and “old” money. It is easy to think of new money fortunes, in the Forbes Real-Time Billionaires[4] list the top entries in order include Elon Musk (self-made), Bernard Arnault and Family (French, started with a modest fortune and turned it into $223 billion, so sort of old and new money), Jeff Bezos (self-made), Larry Elison (self-made), Bill Gates (self-made), Warren Buffet (self-made per Forbes). In fact, if you go down the list and click on each name Forbes will tell you the source of these billionaires’ wealth and in most cases follow that by “self-made”. The billionaires list is international including, for example, Zhong Shanshan, worth $64.6B who dropped out of elementary school in China and worked as a construction worker, newspaper reporter, and beverage sales agent before starting his own bottled water company.

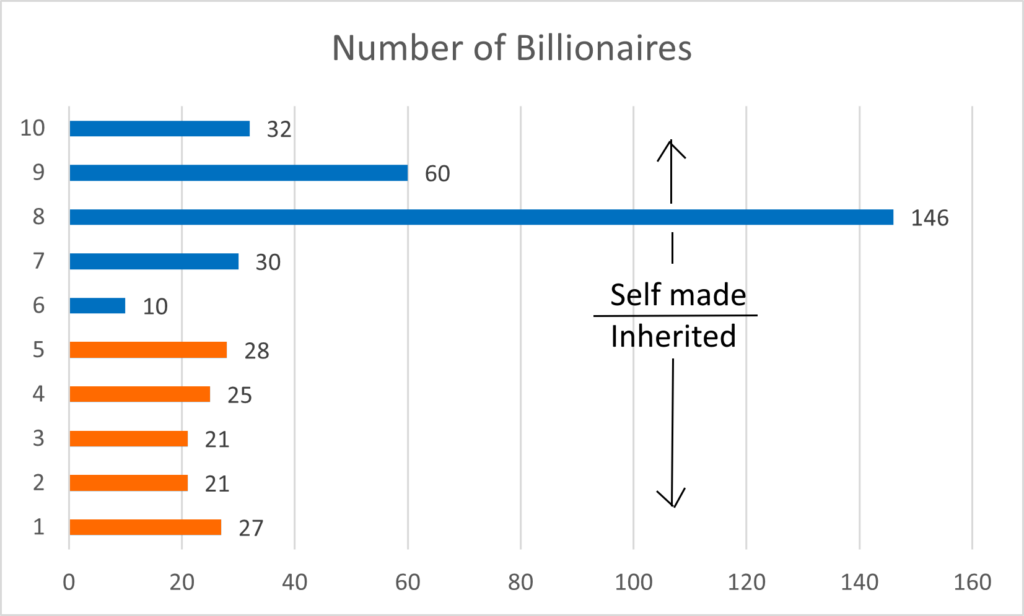

Forbes also publishes the American top 400 list, all billionaires, which includes a “self-made score” which runs from 1 to 10 with scores 1-5 being “inherited” and 6-10 being “self-made”. In 2020 they ranked the 400 like this:

Figure 55: Forbes 400 Richest Americans by “Self-Made” Score: 1-5 being “inherited” and 6-10 being “self-made”. Data Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanponciano/2020/09/08/self-made-score/?sh=3af1105f41e4. WW180

The run-away top ranking is 8, which Forbes describes as “Self-made who came from a middle-class or upper-middle-class background: Mark Zuckerberg & Jeff Bezos”. Scores 9 and 10 are for people who rose from nothing such as Carl Icahn, Patrick Soon-Shiong, George Soros and Oprah Winfrey.

Altogether in 2020, there were 122 on the 400 list who mostly inherited versus 278 who were mostly self-made. Forbes notes:

“When we first created the self-made score, we went back and assigned scores for the members of the 1984 list. Less than half of them were self-made. By 2014, 69% of the list was deemed self-made. Fast forward to the present list, and that figure has inched up to 69.5%. All but one of the 18 newcomers this year [2020] are self-made.”

Some of the inheritors on the list include members of the Mars and Cargill families, a couple of the privately held companies we mentioned earlier in discussing income distribution. It is clear from this Forbes list that “new money” outweighs “old money” in these top fortunes.

While the top of the wealth ladder is heavily populated by people who rose from more or less humble beginnings, overall, there is a strong correlation between your parent’s wealth and your wealth later in life. This is hardly surprising, most wealth is passed on, especially since, in most countries including the US, inheritance taxes are now pretty minimal. Estimates of inherited wealth as a fraction of total national wealth range from 20% to 40%, which of course implies that 60% to 80% of national wealth is “new” wealth but that doesn’t mean that this new wealth didn’t grow from old wealth, indeed much of it did. If you inherit a business worth $20 million (in current dollars) at age 30 and build it to a $400 million business by age 60, you have accumulated $380 million in “new” wealth. Even if you just sold the business and invested the money at a net 8% interest, you would have accumulated $180 million in “new” wealth.

The increasing concentration of wealth observed has many worried that we’re seeing the accumulation of new “dynastic” wealth heavily concentrated in a limited number of families. What does the data say?

To answer this question, one really needs to look at families over time, and such longitudinal datasets which follow the same people over the years are very few in number.

A 2022 Bank of America study of 1,052 people in a representative sample of household with investable assets of more than $3 million, found that 28% of them came from affluence with an inheritance, 46% came from the middle class with some inheritance (or from affluence, but hadn’t yet inherited wealth), and 27% were from middle class or poor families[5]. Net worth of $3 million is close to the average for the upper 10%.

A number of economists have based studies of the source and evolution of higher levels of wealth on a Norwegian administrative dataset that has collected wealth and income information since 1994. This data makes it possible to follow single individuals over their working lifetimes from their twenties into their fifties. Some of the conclusions, at least for Norway[6]:

- Labor income is the most important determinant of wealth up to the 99% level.

- Above the 0.1% level, most wealth (and income) is from equity, in particular privately owned businesses.

- Again, there is a significant mix of “new money” and “old money” among people who in their 50’s are in the top 0.1% of wealth for their age bracket. Of the 0.1%, about one fifth were below the 75% level of wealth in their late 20’s and can be called “new money” while 29.2% were already rich in their late 20’s, almost entirely from family money. Someone who was in the 0.1% when young had 292 times the chance of being in the 0.1% when in their 50’s as the average person[7].

- Few people, five percent, who were in the 0.1% when young fell to the 75% level or below in their 50’s.

- Not surprisingly, those who were wealthy when young saved more and earned higher rates of return on their investments than the less fortunate.

This still doesn’t tell us if we’re building “dynastic” wealth, because we’re not looking across multiple generations, but it’s clear that a significant portion of the wealthy at the 0.1% level come from modest backgrounds, but also that the rich tend to stay that way.

Piketty and others have argued that the recent growth in wealth concentration stems from the rich getting a higher rate of return on their investments than the general growth rate of the economy. Again, in terms of a pie, if the capital slice of the pie grows at a certain rate, the rest of the pie has to grow as fast for the slice to remain proportional. But it looks like much of the recent growth in wealth at the top has come from “new money” rather than returns on “old money”. And the increasing inequality of labor income further contributes to concentration of wealth at the 10% level.

It is only possible to answer the question of what happens to family wealth over time by looking at data, and even then, the answer will be specific to that time period and country. One such study uses the estate data records of families with rare surnames in England between 1858 and 2012. The authors show that there is a high persistence of wealth across generations, but that over long periods of time large fortunes become relatively smaller fortunes.

The average estate of the rich group went from 55 times the average of all estates in the mid 1800’s to 4.6 times the average in 2012[8] . The authors conclude that while the rich are still wealthy 5 generations later:

… there is nothing in English history 1858-2012 to suggest that wealth inheritance itself explains most of current wealth. In all periods wealth creation de novo accounts for most wealth.

They also conclude that the reversion of family lineage wealth to the mean is slow in England because the rich go to good schools, live in rich neighborhoods, and become doctors and lawyers[9]. In short, they have more opportunity to earn and save and build wealth because they have a lot of social capital, which is still quite important in Britain, and probably worldwide.

While this is just one study of a particular population, it jibes well with the Norwegian findings. The picture we get is that it certainly helps to be born into a rich family, that wealth in family lineages dissipates slowly over time on average (yes, many rich get richer), but that there is always substantial new wealth being created in the modern world. Given the rate of technological change, growth rates in the developing world, and the ability of new fortunes to be rapidly built, these conclusions do not appear surprising.

[1] I wish to thank ChatGPT for this list which is only lightly edited.

[2] St Louis FED reporting on results from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Hernandez, Ana, and Lowell R. Ricketts. 2020. “Has Wealth Inequality in America Changed over Time? Here Are Key Statistics.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. December 2, 2020. https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2020/december/has-wealth-inequality-changed-over-time-key-statistics.

[3] Scheidel, W., & Friesen, S. (2010). The Size of the Economy and the Distribution of Income in the Roman Empire Journal of Roman Studies, 99 as reported in https://persquaremile.com/2011/12/16/income-inequality-in-the-roman-empire/.

[4] https://www.forbes.com/real-time-billionaires/#73b3b3aa3d78

[5] “2022 Bank of America Private Bank Study of Wealthy Americans.” n.d. https://ustrustaem.fs.ml.com/content/dam/ust/articles/pdf/2022-BofaA-Private-Bank-Study-of-Wealthy-Americans.pdf.

[6] Mostly from Elin Halvorsen, Joachim Hubmer, Serdar Ozkan, and Sergio Salgado. 2023. “Why Are the Wealthiest So Wealthy? A Longitudinal Empirical Investigation.” FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS. https://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/more/2023-004.

[7] Interestingly, inheritances did not contribute much to “lifetime resources” as recorded in the data. Using other data and inference, the authors concluded that in fact family wealth was being passed to young people at an early age and called this “unobserved intergenerational transfers”.

[8] The research is documented in Clark, Gregory, and Neil Cummins. 2015. “INTERGENERATIONAL WEALTH MOBILITY IN ENGLAND, 1858–2012: SURNAMES AND SOCIAL MOBILITY.” The Economic Journal (582): 61–85. These quotes are from an unpublished paper based on that research.

[9] As quoted in Doward, Jamie. 2015. “Inheritance: How Britain’s Wealthy Still Keep It in the Family.” The Guardian, January 31, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jan/31/inheritance-britain-wealthy-study-surnames-social-mobility.