Labor productivity tells us how much labor it takes to produce something. A horse lets a farmer plow a field much more quickly than he or she could without one and so raises their labor productivity, but at the cost of buying and maintaining a horse.

Throughout most of human history, productivity advancements were modest at best. The modern era of rapid industrial productivity growth began around 1760 when the British started inventing machines to spin and weave cotton and run them using waterpower. This greatly increased the amount of cloth that could be produced and lowered its cost, but also put the hand weavers of Lancashire out of business. The Industrial revolution continued with a suite of technologies advancing in step, including the use of coal and coke in iron making, the steam engine, railroads, the scale production of industrial chemicals and machine tools, and others. Equally as important were earlier and ongoing advances in agricultural productivity resulting from better crop practices, the introduction of the potato and corn and guano fertilizer from the New World, and improved agricultural machinery. These advances in agriculture allowed fewer farmers to grow enough food to fuel a population boom which in turn provided workers for the new factories[1].

In times of full employment, increased productivity raises average real wages and national income. However, working conditions and worker pay during the initial industrial revolution in Britain were abominable. Charles Dickens’ father served time in debtors’ prison and, to keep the family afloat, Charles at age 12 had to work in a factory, 10 hours a day, 6 days a week for the modern purchasing power equivalent of $41 a week, or around 70 cents an hour. Charles Dickens’ novels are an indictment of working conditions in Britain in the mid-19th century. How is it that working conditions were so abominable after at least half a century of industrialization?

A truly impressive number of papers and books have been published on this subject. The consensus is that industrialization did raise real incomes significantly, but that living and working conditions were indeed awful. According to one analysis of available data, between 1781 and 1851 blue collar workers in Britain nearly doubled their real wages, agricultural workers saw an increase of around 60% from a lower base, and white-collar workers’ earnings improved by 150%. Much of this occurred between 1813 and 1851, it took a while for the productivity increases to be reflected in income gains[2]. The increases in white collar wages are a clue to the growth of the middle class which attended industrialization.

That working conditions were lousy can’t be doubted. The work week was generally 10 or more hours a day, 6 days a week. Children were widely employed at low pay, especially in the textile factories, with some as young as 8. Unions were at first outlawed and then widely suppressed. After 1850 the trade union movement started to take off in Britain, eventually giving rise to the Labour party and improvements in working conditions.

The United States remained a largely agrarian society until the end of the 1700’s when the first textile factories were established using “stolen” British technology. In 1800, 80% of US employment was in agriculture, which declined to 50% in 1860 (and less than 2% today). As in Britain, output per capita doubled between 1800 and 1860[3]. After the civil war, US productivity continued to grow with the expansion of the railroads, steel making, the use of standardized parts, the electric motor, the assembly line and many other innovations. As in Britain, workers fought for better working conditions and pay. Political corruption was commonplace and favored monied interests. Huge influxes of immigrants prevented labor shortages and helped settle the West. Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner wrote a book, “The Gilded Age”, a play on “golden age”, that satirized this period of growth, corruption, and wild speculation, which later gave the period its name. Nonetheless the growth was very real: in 2019 dollars, GDP rose from $100 billion to $500 billion from 1870 to 1913 and real GDP per person went from $4,590 to $10,373 despite the massive influx of immigrants from Europe which more than doubled the population over that period[4]. However, wages were still low by today’s standards. A laborer in the US earned about $12,000 a year in 2019 dollars.

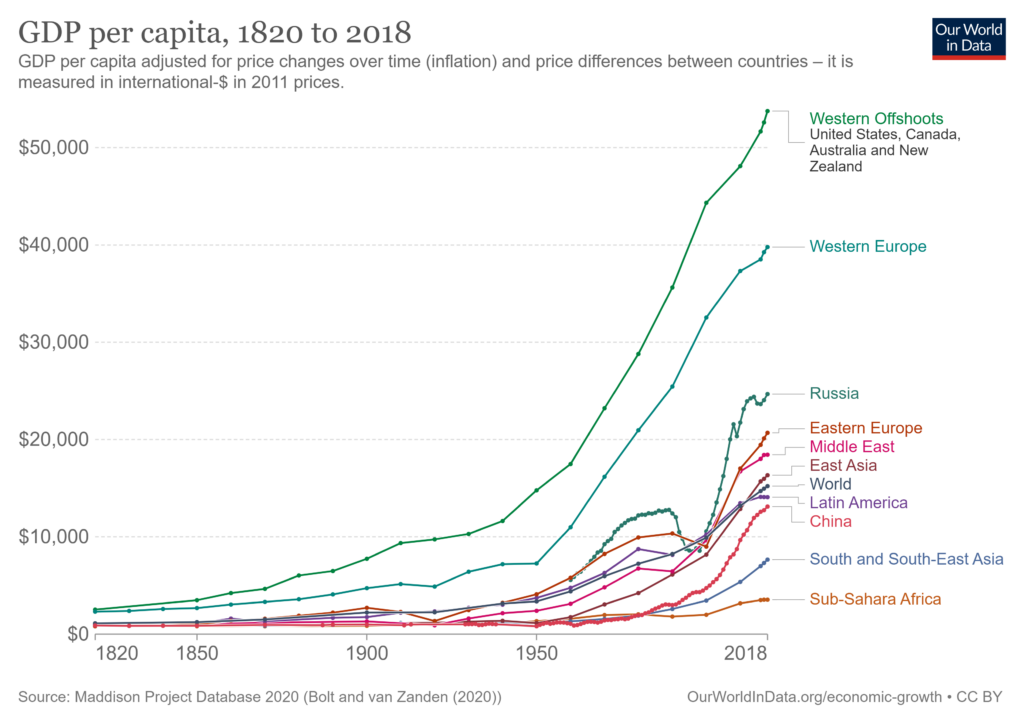

After the Second World War, economic growth accelerated, particularly in the former British colonies of the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and also in Western Europe. Some authors refer to 2nd, 3rd, and even a 4th industrial revolution as new technologies including the already mentioned electric motor, computers, and most recently automation gained widespread use, but these really form a continuing evolution with many other advances in technology, finance, and infrastructure contributing to increased productivity. The growth in productivity since 1950 is unprecedented in world history. The chart below makes this graphically clear[5].

So great were the increases in productivity after the second world war that in 1968 a study by the Southern California Research Council, considering the need for recreational facilities, predicted that by 1985 Americans would have to work only six months a year for the same standard of living that they had then. The study envisioned Americans taking up to 6-month vacations, shifting to shorter work weeks, continuing full time for additional income, or retiring as early as age 38.

It actually took until 1998 for US inflation adjusted GDP per capita to double from 1965. It took longer (until 2010) for GDP per worker to double. This time lag was due to the fact that there were more people working, especially women, in 1998 than in 1965[6]. So instead of the rosy prediction of people working fewer hours as productivity and output increased, there were actually more people working in 1998, and indeed 2019, than in 1965! Why? Did everyone want twice as much “stuff” in 1998 and nearly three times as much “stuff” in 2019 as in 1965[7] and place a really low value on free time? Is there inherently something wrong with the way real GDP is measured? Was this due to changes in income distribution and benefits? We will try to answer these questions in the coming chapters. To get a feel for scale, GDP in 2019 in the US was around $142,540 per worker, or $285,000 for a two-worker family[8]. Of course, this is the average value of output.

[1] Culture also played a significant role in nursing the revolution.

[2] Lindert, P. H., & Williamson, J. G. (1983). English Workers’ Living Standards during the Industrial Revolution: A New Look. The Economic History Review, reprinted in Mokyr, Joel. 2018. The Economics of the Industrial Revolution (Routledge Revivals). Routledge.

[3] The labor and growth estimates for 1800 – 1860 are from Weiss, Thomas J. 1992. “U. S. Labor Force Estimates and Economic Growth, 1800-1860.” American Economic Growth and Standards of Living before the Civil War. https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c8007/c8007.pdf.

[4] Tables A1-c Maddison, Angus. n.d. “The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective” Oecd-Ilibrary.org. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/the-world-economy_9789264189980-en. CPI adjusted from 1990 to 2019.

[5] The differences by country in income shown here are ameliorated by greater local purchasing power in poorer countries. Simply put, a dollar’s worth of local currency often buys more in a poorer country than the same dollar would in a richer country. This is especially true of staple items. Economists call this “purchasing power parity” (or PPP) and when comparing per capita GDP between countries, PPP adjustment is often made. Of course, “per capita” GDP says nothing about income distribution in a country.

[6] As a percent of the population over 16. In 1965 39% of women were in the labor force, in 1998 that percentage had increased to 60%. Men’s participation rate dipped from 81% to 75% over the same period. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Participation Rate [CIVPART], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CIVPART, November 14, 2022.

[7] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real gross domestic product per capita [A939RX0Q048SBEA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A939RX0Q048SBEA, November 13, 2022.

[8] BEA, BLS 2019 GDP is $21,381 billion, population 328.239 million, 150 million workers.