Any attempt to look at “world economics” broadly in a reasonable number of pages will necessarily be an incomplete outline. We’ve looked at some widely accepted tenets of modern economics and examined data and research that looks at the drivers of economic growth, the distribution of income and wealth both within countries and worldwide, and some of the issues of globalization and sustainability that are hallmarks of our times. We conclude that humanity forms one highly interconnected economic system which is rapidly running into the limits of what our planet can support. What follows is a summary of a summary.

Humans Dominate the Planet Physically

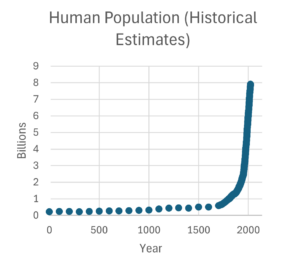

We have entered the Anthropocene, the geologic age named for humans, with a vengeance[1]. Throughout much of human history, population growth was checked by disease, famine, and war. With the advent of the scientific and industrial revolutions death rates declined precipitously thanks to better hygiene, vaccinations, increased food production and better transport. In Europe, birth rates of 30-35 per 1000 inhabitants per year were essentially matched by death rates of 30 per 1000 in 1800. By 1900 the death rate had halved, but birth rates remained high[2]. The result has been an explosion in the human population.

Not only is the human population, at 8 billion and growing, far greater than that of any large species before us, but the animals we raise for food outweigh all wild birds and large mammals by a factor of ten[3].

Not only is the human population, at 8 billion and growing, far greater than that of any large species before us, but the animals we raise for food outweigh all wild birds and large mammals by a factor of ten[3].

Our waste gases are changing the climate of the planet at a rate not seen since about 50 million years ago when there were major ongoing volcanic eruptions. While productivity increases in agriculture have allowed us to grow vastly more food on each hectare of land, increasing demand for meat as the world grows richer would require the use of more arable land than exists on the planet on present trends. As a result, the amount of wild land on earth has fallen and with it the populations of wild animals. Humans are indeed now “stewards of the earth”[4]. No one nation can take on that role by itself, it will require us to work together to reach a future that is within the ability of the earth to support.

Of course, this growth in human population is very much a success story for us and our technology. We are a spectacularly successful species. Fortunately, as we have seen, the birth rate falls as people become better off. The worldwide birth rate has fallen from over 5 births per woman in 1960 to near the replacement rate of 2.3 births per woman now. This is already causing a slowdown in population growth with “peak human” predicted to be in the range of 10 to 11 billion people, but that is still a huge increase. Reaching a sustainable future is well within the capability of humanity even with current technology. The investment required is also quite manageable and pays huge future dividends. But at present the effort is progressing too slowly.

The World Economy is Thoroughly Globalized and It’s Not Going Back

Economically the world has been knit together through “globalization”. Lower transport costs, financial fluidity, the rapid dissemination of technology, and communications that make it easy to integrate production and services across the globe have created an interdependent world economy in which, for most countries, the value of imports and exports combined is around half the size of their GDP. It is highly unlikely that globalization will give way to economic isolationism: smaller countries simply cannot produce everything they need and larger countries such as the US, where trade is 25% the size of GDP, gain enormously from it. Since trade is often a contentious issue in the US and other “advanced economies” we’ve looked in depth at both the theory and economic data on trade and found that the dislocations often attributed to trade are, in fact, mostly due to automation and productivity increases. While it took 80% of the population to grow food in the US in the 1700’s, it now takes less than 1% of the population. Automation has also greatly reduced the need for labor in manufacturing. Manufacturing accounted for about 30% of employment in the US in 1960 and about 8% today. Some part of that decline, perhaps one fifth at one point, was trade related, but even in advanced countries such as Germany with a huge trade surplus the decline in manufacturing employment has been similar. Overall trade has enormously benefited the inhabitants of rich countries, 80% of whom now work in “services”, through lower prices and a wider selection of goods and services. Unfortunately, the decline in manufacturing employment, regardless of cause, has created economic hardships for displaced workers and specific regions. It is important to understand the causes, however. Trade is often scapegoated, and its benefits underappreciated in the wealthy countries. While people can see rising prices, prices that stay the same over time, or fall in real terms, aren’t so easy to see.

Developing countries also have benefited from trade. It has provided funding, through foreign investment, for economic development and capitalization. We’ve looked a bit at this process in China, where foreign firms invested in clothing manufacturing in the special economic zones, and later in electronics.

One of the benefits of free trade is that it naturally leads to the efficient production of goods and services, an effect we discussed in terms of both theory – comparative advantage – and in the data. When trade barriers are removed there is an initial “trade shock” which leads to affected industries and their workers suffering, but in the end overall productivity increases. It is the memory of this adjustment period that lingers, but, in a world of lower trade barriers, countries’ economies adjust and then evolve more naturally in line with productivity changes. China still produces a lot of clothes, but a lot of that business has moved to what are now lower labor cost countries and China has moved up the productivity ladder to produce more capital-intensive goods.

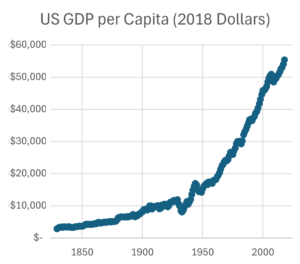

Productivity Has Made the Rich Countries Rich

We in the “advanced economies” are vastly richer than we were 100 years ago, on average. At least so the statisticians say, we’ll get into why it may not feel that way in the last chapter. The chart below shows the long term estimated GDP per capita adjusted for inflation in the US. The production of food and manufactured items is so efficient now that most people work in service jobs in advanced economies. Income and productivity are directly related, the more output value you can produce per hour of work, the higher your labor productivity and usually your income. We’ve noted that while most of the labor productivity gains are due to improved technology and scale, some of the gains are due to increased use of capital. That means that wages can’t go up at quite the same rate as labor productivity gains but increases in productivity [RF1] remain the main driver of income gains. Historically many services have had lower productivity growth than  manufacturing, so we might expect overall productivity and income growth to be slower in the future in advanced economies. AI may upend that expectation if it significantly increases major service sector productivity.

manufacturing, so we might expect overall productivity and income growth to be slower in the future in advanced economies. AI may upend that expectation if it significantly increases major service sector productivity.

Productivity is Rising in the Developing Countries but Unequally

Worldwide, productivity growth is faster in what are called the developing countries than in the advanced economies. No surprise because capital investment in such an economy can leapfrog directly to the latest technology, while advanced economies are already there.

Because income is closely linked to productivity, this means that income is also rising in developing economies, with a direct relationship between capital investment, productivity, and income. But there are large differences between countries in their rate of productivity growth, and even countries with high productivity growth rates, such as China, are expected to take decades to catch up to still growing advanced economy per-capita income levels. Does this matter? We’ll consider that in the final chapter, but it does mean that “labor” will continue to be cheaper for a long time in the developing economies than in countries on the productivity frontier. Labor intensive businesses will move around the globe continuously as countries climb the productivity ladder, other things being equal.

Other things are of course not equal, which explains why productivity is growing faster in some developing countries than others. Economists find that faster growing countries have been characterized by better initial education levels, greater political stability, and governance, and greater or deepening economic complexity. The last factor is almost tautology: it says that as your economy gets more diversified it develops synergies that can increase growth. With stability and a reasonable level of business friendliness, a market economy will attract investment and participate in “global value chains” (i.e. trade other than basic commodities) which in turn will fuel further growth. Corruption, wars, and lack of an educated workforce will impede investment whether foreign or domestic. Urbanization, the flow of people from low productivity agriculture to cities, is as much an effect of productivity growth and industrialization as it is a cause.

On top of these drivers of per capita economic growth sits demographics: if your population grows faster than your economy, people get poorer in the aggregate. Low productivity growth rates in Sub-Saharan Africa are made worse by high birth rates. In many of the advanced economies, and in China, the aging population threatens aggregate productivity: retirees who don’t work add to population but not to output. But demographics don’t directly affect per worker productivity.

Low productivity growth rates plague some of the poorest countries in the world.

Income and Wealth Inequality Is High

The rich countries are very rich compared to the poor countries. The median daily cash income worldwide in 2018 was $7.50 in US purchasing power according to the World Bank. Try to survive on $7.50 a day in the US! The poor worldwide tend to live together in extended family groups to save money and pool resources. While they often don’t have legal title to their land, in rural areas they farm small plots and own their house, albeit a mud hut or shanty. In Udaipur, a tourist destination region in India, a survey of poor households found that 14% owned a bicycle, 10 percent had a chair or a stool, and 5 percent owned a table. Fewer than 1 percent had an electric fan, a sewing machine, a bullock cart, a motorized cycle of any kind, or a tractor. No one had a phone[5].

The rich countries are indeed much richer than the poor countries. Per capita GDP in the US was $62,459 in 2018 while in India, a lower-middle-income country, it was a tenth of that at $6,689 in US purchasing power (and lower in dollars at exchange rates).

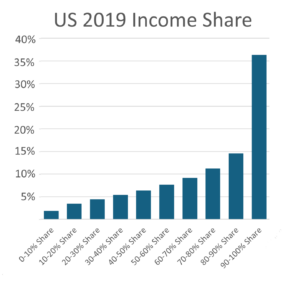

The differences in income between countries, large as they are, are dwarfed by the differences between families within countries or for that matter across the globe. In the US, one of the richest countries on earth, about 12% of the population falls below the official poverty line, which is an estimate of the point below which a household of a given size has pre-tax cash income insufficient to meet minimal food and other basic needs. Meanwhile at the other extreme are families making many millions of dollars in income annually and even more in capital gains.

The differences in income between countries, large as they are, are dwarfed by the differences between families within countries or for that matter across the globe. In the US, one of the richest countries on earth, about 12% of the population falls below the official poverty line, which is an estimate of the point below which a household of a given size has pre-tax cash income insufficient to meet minimal food and other basic needs. Meanwhile at the other extreme are families making many millions of dollars in income annually and even more in capital gains.

The chart shows the fraction of income going to each decile of households, which also gives the relative income of households. As we discussed, the top decile certainly sticks out, and when that is analyzed in detail there is an equally skewed distribution within just the top ten percent. We also noted (Figure 34) that taking a tiny slice of the top ten percent income bar and adding it to the lowest income bars would eliminate poverty. Transfers and taxes on declared income have only a modest effect on income distribution in the US.

Worldwide, household income distribution is similarly skewed with forty percent or more of national incoming going to the top ten percent.

Wealth distribution is even more concentrated than income distribution worldwide and within countries. Worldwide the top ten percent own three quarters of the wealth.

Migration, the Good the Bad and the Ugly

The world has always had migrations as people seek to better their fortunes or escape wars and persecution. There are nearly 300 million migrants in the world today, more than half of whom are “guest workers”. Europe and North America receive and host the most permanent migrants, although other countries host more as a percentage of population. Some countries such as the oil rich kingdoms of the Middle East rely heavily on migrants for labor: nearly ninety percent of the population of the United Arab Emirates is composed of immigrants who are in the country under temporary labor contracts. Due to the decline in birth rates and the aging population in many advanced economies such as the United States and Germany, migrants make the difference between a declining workforce and a stable one. Migrants to the US are credited with preventing a post COVID recession by filling jobs for which businesses couldn’t otherwise find workers[6].

New immigrants’ skills often compliment the native-born population, agriculture in the US relies heavily on immigrants, but immigrants may also compete for some jobs such as in construction. As with trade, this additional supply of labor can dampen wage growth in those occupations but that reduces the prices of the affected goods and services for everyone else. Economic studies show that over a couple of generations new immigrants in the US and many other advanced economies become indistinguishable economically from the general population, so the long-term effect of immigration is a growth in the population and an equal growth in GDP.

In addition to job competition, new immigrants compete for shelter which can raise housing costs. In the US, immigration has an overall positive effect on tax collections at the Federal level, but state and local governments bear local service costs such as for education.

From the immigrant’s point of view, when they move from a low productivity country to a high one, their productivity and income prospects improve greatly. That is also the world economic effect: such immigrants improve overall global GDP and productivity and send “home” much needed earnings.

The ugly side of immigration includes the wars and starvation that force many to risk their lives, the perennial negative politics in receiving countries, and the exploitation of migrants both on their way to their new homes and once they get there. Similarly to trade, in-migration to the wealthy economies has huge, largely underappreciated benefits and obvious social impacts which some view negatively. Surges in migration, like sudden changes in trade, create ethical, political, and short-term economic problems.

Ideally it would be great if the world could do a better job of controlling the drivers of immigration, such as extreme income inequality, wars, repression, and agricultural failures intensified by climate change. We’ll discuss some ideas in the final book.

[1] The Anthropocene Epoch has not been approved yet as an international standard, but will be once a more or less irrelevant start date is agreed upon.

[2] Van Bavel, J. 2013. “The World Population Explosion: Causes, Backgrounds and -Projections for the Future.” Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn 5 (4): 281–91.

[3] Humans make up just 0.01% of Earth’s life – what’s the rest? – Our World in Data

[4] In addition to the science, the major religions all preach that humans must care for the earth. See Religions and the Environment (UN) and Opinion: Christians Are Called To Be Good Stewards Of The Earth (Liberty University student newspaper).

[5] Banerjee, Abhijit V., and Esther Duflo. 2007. “The Economic Lives of the Poor.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 21 (1): 141–67.

[6] Rovella, David. 2024. “US Companies Plead for More Immigrants Amid Tight Job Market.” Bloomberg News, March 5, 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2024-03-05/bloomberg-evening-briefing-us-companies-want-more-immigrants. The availability of work of course also attracted migrants.

[RF1]See McKinsey article on labor share