Here again is our table of employment changes from 1960 to 2010 and 2020 in the United States.

| Industry Sector | % of Empl 1960 | % of Empl 2010 | % of Empl 2020 | % Chg 1960 – 2020 | Jobs lost/gained thousands* |

| Services-providing, excluding special industries | 53.7% | 79.8% | 80.0% | 49.0% | 37,401 |

| Wholesale trade | 4.1% | 3.8% | 3.7% | -9.0% | -541 |

| Retail trade | 8.5% | 10.2% | 9.7% | 14.0% | 1,648 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 3.5% | 2.9% | 3.6% | 3.0% | 142 |

| Information | 2.6% | 1.9% | 1.8% | -32.0% | -1,195 |

| Financial activities | 3.9% | 5.4% | 5.7% | 47.0% | 2,604 |

| Professional and business services | 5.7% | 11.8% | 13.2% | 133.0% | 10,709 |

| Educational and Health | 4.5% | 12.9% | 13.9% | 210.0% | 13,416 |

| Leisure and hospitality | 5.3% | 9.2% | 8.7% | 65.0% | 4,854 |

| Other services | 1.8% | 4.2% | 3.9% | 122.0% | 3,043 |

| Federal government | 3.6% | 2.1% | 1.9% | -48.0% | -2,471 |

| State and local government | 9.3% | 13.7% | 12.4% | 33.0% | 4,416 |

| Notes | |||||

| * Jobs lost/gained if employment distribution was unchanged from 1960. Total US Employment was around 150 million in 2020. This measure is only a baseline for comparison. All data except agriculture are from the BLS series. Agriculture is from OECD data. Transportation and warehousing 1960 is estimated from 1972 data. | |||||

In the US, the services sector employment as a whole has grown from 53.7% of the workforce in 1960 to 79.8% of the workforce in 2019. The biggest growth has been in Education and Health, which went from 4.5% to 13.9% of the workforce, and in Professional and Business Services, which grew from 5.7% to 13.2% of the workforce. The BLS didn’t separate out Education until 1987, but currently, Education is one-sixth the employment of Health. Professional and Business Services includes a grab bag of occupations: accountants, architects, lawyers, scientists, managers, janitors, security guards, office clerks, programmers, landscaping workers, etc. All of these service sectors gained employment share except for Wholesale Trade, Information, and the Federal Government. Some of these exceptions seem surprising so let’s take a closer look.

“Information” includes publishing, motion pictures and recording, telecommunications, and data processing (which includes Facebook and Google, for example). That this sector would have lost employment share since 1960 seems strange but publishing has lost jobs and computer programming isn’t included here, it’s under Professional and Business Services. Amazon’s roughly one million employees fall in multiple categories to reflect its various businesses.

Perhaps most surprising is that Federal government employment share has declined 48% while State and local government share has increased 33%. Civilian employment in the Federal Government went from 3,370,000 in 1945 to 2,161,000 in 1960 and stood at 2,191,000 in 2019. Military personnel headcount went from 2,476,000 in 1960 to 1,388,000 in 2019[1].

The rest of the “services” super sector of the US economy saw increasing employment shares over the period, often large ones. The US pattern of services employment growth at the expense of the agriculture and manufacturing sectors is typical of other high-income countries including Western Europe, Japan, Australia, Canada, and others (see Figure 9 ). In these countries services now account for over seventy percent of employment. In middle-income countries, which include most of the rest of the world, both manufacturing and services are growing while agricultural employment shrinks. In China services have also been growing faster than manufacturing and now account for the largest share of employment at 47%[2].

It is pretty clear that agriculture and manufacturing currently require fewer workers than in earlier times, and that “service” sector employment will continue to grow in developing countries. We have seen that, in the advanced economies, productivity and employment share in agriculture and manufacturing have not changed much in the last decade.

The wealth of a country is often given in terms of GDP per capita and its productivity in terms of GDP per worker. Historically agriculture and manufacturing productivity increases have fueled enormous growth in the developed world. Now that these sectors account for a relatively small proportion of employment, and conversely, labor constitutes a modest part of the cost of agricultural and manufacturing output, increased growth in wealth and productivity falls largely to services. What can we say about productivity growth in services?

Productivity in many service sector industries is hard to measure and, in some cases, simply unlikely to occur. An example often used in economics is haircuts. Do you really want your hairdresser to cut your hair a lot faster? Can your waiter deliver the plates faster without destroying the ambience?

Productivity is the ratio of output to labor input (labor productivity) or a set of inputs (total factor productivity). In the case of many services, it is difficult to quantify the value of output meaningfully over time for an industry. To quote a 1999 Bureau of Labor Statistics article which is still true today:

…for a surprisingly large number of service-producing industries there is a lack of agreement among economists on the best definition of output. Economic literature has produced no consensus definitions for banking, insurance, other financial services, medical care, a variety of business and personal services, or retail and wholesale trade[3].

The same report illustrates this by looking at the problem of quantifying the output of the banking industry:

Five different treatments of bank deposits have been recommended: deposits are treated, variously, as inputs, outputs, both inputs and outputs, either inputs or outputs and neither inputs nor outputs. Viewed in the light of this lack of agreement on the measurement of banking output, it is easy to understand why both the BEA and the BLS have opted for straightforward and simplified means of producing data on banking output. The BEA procedure extrapolates part of the bank output data by the use of input data and the BLS banking industry productivity measure includes an output measure that rests on counts of specific banking industry transactions[4].

A straightforward example of the problem of measuring productivity in banking over time is the emergence of the ATM. The ATM made it possible for consumers to do their banking 24/7 and in many locations. The cost of installing and maintaining ATMs [RF1] is an expense which if not matched by cost savings elsewhere, or some valuation of the “worth” of this service to the consumer, will lower the computed productivity of retail banking, even though consumers are undoubtedly benefitting. This problem of valuing a bundle of changing services over time has some economists convinced that computing meaningful productivity over time for many services is impossible. We encountered the same problem in trying to compare the output of manufactured goods over time. What is the value of all the electronics in a modern car and how do you compare that to a 1960’s car? Is a laptop that is 100 times as fast as an older one really “worth” 100 times as much? In some service industries these problems can become overwhelming.

Instead of looking directly at productivity let’s look at prices. The table below shows how the prices of goods and services bought by consumers in the United States have changed since 1960, along with per capita consumption in 2019. Green rows indicate where prices have come down, and pink rows show where prices have gone up since 1960.

Table 4: US Personal Consumption by Industry

| Personal consumption category by industry | Per capita consumption 2019 | 1960 % of Spend- ing | 2019 % of Spend ing | Price Change 1960 to 2019 |

| Overall Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) | $43,847 | |||

| Goods | $13,611 | 53% | 31% | -47% |

| Durable goods | $4,599 | 14% | 10% | -77% |

| Motor vehicles and parts | $1,564 | 6% | 4% | -50% |

| Furnishings and durable household equipment | $1,095 | 5% | 2% | -74% |

| Recreational goods and vehicles[5] | $1,279 | 2% | 3% | -96% |

| Other durable goods | $661 | 1% | 2% | –57% |

| Nondurable goods | $9,012 | 40% | 21% | -18% |

| Food and beverages (groceries) | $3,133 | 19% | 7% | -5% |

| Clothing and footwear | $1,210 | 8% | 3% | -72% |

| Pharmaceutical and other medical products | $1,627 | 1% | 4% | 11% |

| Gasoline and other energy goods | $1,026 | 5% | 2% | 60% |

| Other nondurable goods | $2,016 | 7% | 5% | -4% |

| Services | $30,236 | 47% | 69% | 49% |

| Household expenditures for services (per capita) | $28,900 | 45% | 66% | 57% |

| Housing and utilities | $7,815 | 17% | 18% | 35% |

| Health care | $7,470 | 5% | 17% | 162% |

| Transportation services | $1,505 | 3% | 3% | 25% |

| Recreation services | $1,772 | 2% | 4% | 18% |

| Food services and accommodations | $3,064 | 6% | 7% | 61% |

| Financial services and insurance | $3,560 | 4% | 8% | 58% |

| Other services (includes Education) | $3,713 | 8% | 8% | 40% |

| Nonprofit expenditures for households (mostly Education and Health)[6] | $1,337 | 2% | 3% |

Source: BEA Table 2.3.4U. Price Indexes for Personal Consumption Expenditures by Major Type of Product and by Major Function and Table 2.3.5U. Personal Consumption Expenditures by Major Type of Product and by Major Function. CPI-U is used as the deflator. The “relative price change” is explained below.

Goods in this table have all come down in price with the exception of fuels and medical products, and most services have gone up in price, most substantially in health care. Housing and health care services are the two biggest consumer spending categories in 2019 at over $7,000 per capita each ($61,140 combined for a family of 4) in the US. Surprisingly, housing shows only a modest price increase between 1960 and 2019 but see the discussion below. Education isn’t shown separately on this chart because it is around 2% of consumer spending ($308 billion out of total consumer spending of over $14 trillion, but this doesn’t include public school expenditures or $85 billion in non-profit spending). Health care spending includes payments by insurance and government. The 2019 total “average” per capita annual personal spending of $43,847 comes to $175,388 for a family of four. That is an interesting number we’ll look at more later.

| Notes on this Table A few notes on the values in this table should be kept in mind. First, trade is clearly an important factor in lower goods prices in some sectors such as clothing, and Personal Consumption Expenditures include imports. However, the US still produces most of its own goods, is a large exporter of goods, and, with increases in productivity flowing through to lower prices, relative prices capture relative productivity changes for domestic production. Second, all price increases and decreases are shown relative to the overall Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index[7]. The overall PCE Price Index is like the better-known Consumer Price Index (CPI) but is preferred by the Bureau of Economic Analysis which produces the numbers in the table. Like the CPI, the overall PCE index indicates how much overall consumer prices have gone up year to year. The overall PCE index in 2019 was 6.7 times higher than in 1960 due to inflation. In the table anything that went up less than 6.7 times thus got cheaper relative to the general cost of living. So, for example, Motor Vehicles and Parts went up only 3.3 times so the price of cars fell by 50 percent relative to the overall cost of consumer goods and services. The last column of the table shows whether each category went up as much as inflation (6.7 times) or less and by how much. Did cars really get cheaper? Yes, relative to inflation, but we also have to consider incomes. If you are old enough to have worked in 1960 and were still working in 2019, you’d need to make 6.7 times as much in 2019 as you did in 1960 to have kept up with inflation. In a more realistic sense, someone doing what you did at the same age in 1960 would have to make 6.7 times in 2019 what you made then in order to have not lost to inflation. The PCE or CPI tells us about the cost of living but not about wages which we’ll look at later. Another note of caution – pricing services has the same issues as trying to calculate services productivity, indeed calculating output prices is one step in calculating productivity. As the nature of the service changes, a meaningful valuation of output requires trying to put a value on service components such as the ATM mentioned earlier. As a check, the chart also shows the actual percentage of consumer spending on each category. While what is available to the consumer changes over time, as do budgets, preferences, income and age distribution, the changes between 1960 and 2019 tell us a similar story to prices. Spending on goods has fallen from 53% to 31% of the household budget while services consumption has gone up proportionately. Families, in total, spend less than half as much on food shopping and clothes now as they did in 1960, more on fuel, and over 300% more on healthcare. |

Calculated productivity and prices, and actual consumer spending, confirm that we are now spending much more on services than 50 years ago and that productivity growth in some major services is considerably slower than the growth in manufacturing productivity in prior times. Unless productivity growth in services picks up, the result will be slower increases in GDP growth per capita and worker, and accordingly slower growth in average real (i.e. inflation adjusted) incomes. This applies to all advanced economy countries. Developing countries that are still expanding their industrial base and modernizing their agriculture can expect higher productivity and per capita income gains.

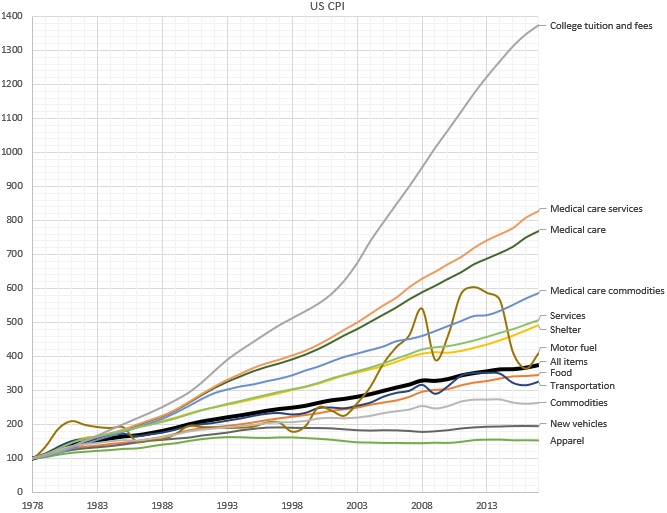

The chart below graphically shows the change in US prices since 1978 as calculated by the BLS[8]. Note that these prices are not adjusted for general inflation, rather they show price inflation for groups of products or services. For example, a new vehicle in 2017 costs roughly the same dollar amount as one in 1998. The “All Items” line shows the general rate of inflation, goods or services above that line got relatively more expensive, and stuff below that less so. (If you read the footnote, you will start to appreciate that there are multiple ways to compute the price changes that we consumers face, and these can lead to substantially different inflation numbers. This will be important when we look at how income changes stack up against price changes. For now, both ways to compute price changes agree on our major conclusions that services have gotten more expensive while products have gotten less so.)

Figure 15: Price index (1978=100) not inflation adjusted. Source: By BoH – data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75468943. WW151

In terms of spending the two largest cost items in services are health care and housing at over $7,000 per person in 2019. Indeed, the cost of an HMO plan for a family of four is over $28,000 according to industry sources[9]. Let’s look a bit more deeply at these two hot topics, starting with health care.

Healthcare Costs

Table 4 breaks down personal consumption expenditures by goods versus services, and health care includes both. To get a more complete picture of health care costs in the US, we have to look at personal expenditures by function. The BEA also provides a table for this.

Table 5: Table: US Personal (per capita) Expenditures on Health, and Price Changes.

| Health Product or Service | Price Change 1960 to 2019 (inflation adj) | 1960 per capita (in 2019 dollars) | 2019 per capita (in 2019 dollars) | Spending increase per capita |

| Health (total) | 126% | $996 | $9,194 | 923% |

| Medical products, appliances, and equipment | ||||

| Pharmaceutical products | 12% | $161 | $1,608 | 998% |

| Other medical products | -47% | $5 | $19 | 392% |

| Therapeutic appliances and equipment | -28% | $44 | $214 | 488% |

| Health Services | ||||

| Physician services | 94% | $283 | $1,753 | 619% |

| Dental services | 173% | $98 | $418 | 428% |

| Paramedical services (home health, labs) | 67% | $68 | $1,211 | 1772% |

| Hospitals | 251% | $308 | $3,390 | 1102% |

| Nursing homes | 140% | $29 | $581 | 1983% |

Source: BEA Table 2.5.5. Personal Consumption Expenditures by Function and Table 2.5.4. Price Indexes for Personal Consumption Expenditures by Function, inflation adjusted using overall PCE.

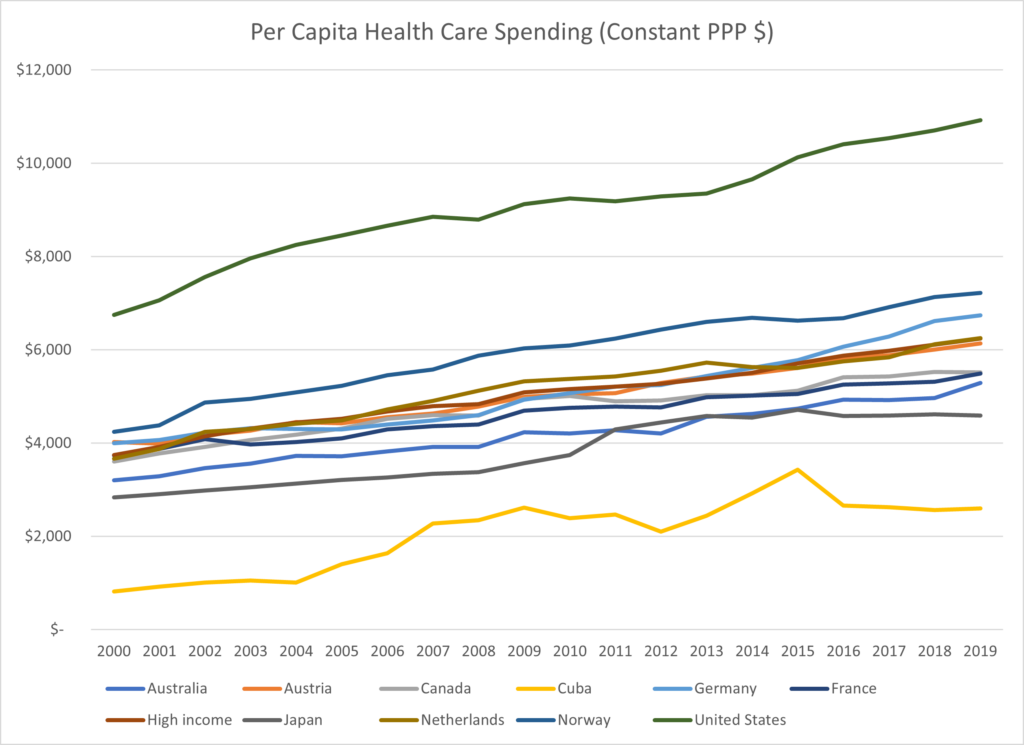

Overall healthcare prices have gone up 126% more than general inflation from 1960 to 2019. All the services have gone up significantly in price. But in addition to the price changes there has been an enormous increase in consumption of healthcare. Pharmaceutical prices, mostly generics, have only risen slightly since 1960 but we’re spending 10 times more on them per capita![10] While hospitals charge an inflation adjusted 251% more now for similar services as in 1960, we’re also using more than 10 times as much of this resource[11]. As a result, health care has grown from 6% of personal consumption spending to 21% in the US. The subject of healthcare economics requires a large volume, or several, on its own, so just a few additional notes. Healthcare costs have risen worldwide as shown in the World Bank data charted below.

Figure 16: Healthcare costs over time. The US is the top line. Source: World Health Organization Global Health Expenditures Database accessed through World Bank data portal. WW152

While per capita health care costs are rising in other countries, the US is clearly in a league by itself[12]. Despite the outlier spending, the Commonwealth Fund ranked 11 countries in healthcare outcomes using several metrics and concluded:

“Among the 11 nations studied in this report – Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, France, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States—the U.S. ranks last, as it did in 2010, 2007, 2006, and 2014”[13]

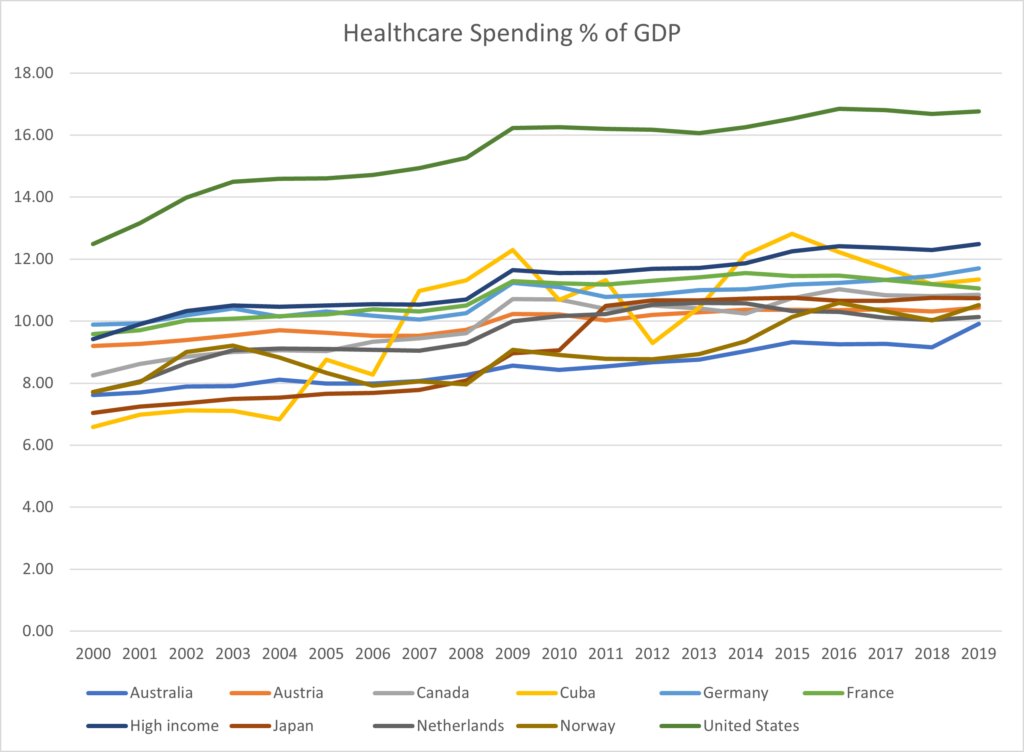

We can also look at the percentage of GDP devoted to healthcare by country.

Figure 17: Source: World Health Organization Global Health Expenditures Database accessed through World Bank data portal. WW153

Again, the US stands out.

Now we might suppose that greater healthcare utilization explains the greater per capita cost in the US, but it turns out that utilization is just as high in other countries. Furthermore, other countries insure virtually 100% of their citizens, while in the US about 91% of the population is insured, usually with copays. There are two main reasons for higher US healthcare spending:

- Higher costs for pretty much everything medical in the US compared to other countries.

- Inefficiency: about 30% of US Healthcare spending goes to administration largely because of an extremely convoluted billing structure[14]

For a brief overview of why healthcare costs more in the US, see the excellent article “6 Reasons Healthcare Is So Expensive in the U.S.” in Investopedia[15].

| Why Free Market Economics Fails to Control Healthcare Costs in the US While this section looks at data, I would like to briefly review some of the economic theory related to healthcare, and why market competition fails to work to drive down healthcare costs. Healthcare tends to be price insensitive, or as economists put it, demand is inelastic with respect to price. In short, if you need a pill or an operation, especially for a life-threatening condition, you would probably not be looking closely at the price. When was the last time you “shopped around” for a medical procedure? If you are covered by insurance, you have little incentive to “shop” because your co-pay would be the same in any case. Furthermore, you probably don’t want to travel far from home for an operation, so the supply side is limited, there are often local monopolies. Market pressure only works to drive down costs if there are many buyers (there are) and many suppliers (there aren’t) and the buyers have an incentive to shop around (they don’t). You might think that health insurance companies would be concerned about price. If they can insure a company’s workforce for less than their competitors, they can boost sales. But insurance companies don’t have all that much bargaining power with large providers. The providers can set their rates for various services and simply “not accept” an insurance plan that doesn’t pay enough. That plan might be cheaper, but subscribers might want specific hospitals which have a “good reputation” or are local. The suppliers retain significant power to shape the market. Finally, the proliferation of insurance companies in the private sector, and the complex financial arrangements, create very significant administrative costs. Fraud also adds to costs. Pharmaceutical economics also points to market monopoly power. While the BEA/BLS calculate that overall pharmaceutical prices have pretty much gone up with inflation between 1960 and 2019, most of that can be attributed to generics: three quarters of prescriptions are filled with generics, but generics only account for one quarter of the drug market in dollars[16]. Patents are a state intervention in free markets which grant inventors a temporary monopoly in order to foster innovation. However, demand for many pharmaceuticals, unlike say a better mousetrap, is also inelastic, meaning that there is essentially no upper limit to what the company can charge, and some companies have clearly abused that situation. It is important to foster and fund innovation, but the drug companies have found many ways to game the patent system in ways that strictly increase profits even for drugs such as insulin that were invented more than 100 years ago[17]. In any case, pharmaceuticals offer a great example of the power of competition. An FDA study[18] finds that drug prices fall 39% when a single generic manufacturer starts competing with a branded drug. With two competitors the price falls 44%, with four competitors it falls 79%, and with six or more competitors the price falls an astonishing 95%. In sum, healthcare and pharmaceutical pricing reflect monopoly power which helps explain why the market has failed to control costs and promote efficiency in the United States[19]. |

Housing Costs

Unlike healthcare, there is a robust market in housing with many buyers and sellers, abundant information, and greater elasticity of demand in response to prices. However, everyone has to live someplace, and an imbalance between supply and demand in a locality can cause prices to quickly escalate as we’ve seen of late.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis calculates that housing costs increased a modest 5% relative to inflation between 1960 and 2019, as shown in Table 4. That number is based on rents and, for homeowners, on rental equivalence, as well as other costs such as utilities. The calculation involves the detailed analysis of low-level Census data[20]. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also provides inflation indexes for various components of housing, the broadest of which is “Shelter” which, like the broad CPI, is based on “urban” consumers[21]. That cost measure increased by more than a factor of 12 between 1960 and 2019, or40% more than CPI inflation[22]. The Census also publishes data on rents from the American Housing Survey. That survey is designed to track all US housing through a representative sample of housing units. The median “gross” rent in the American Housing Survey in 1960 was $71 while the median in 2019 was $1071 which is a ratio of 15, or a 73% increase over inflation as measured by the CPI[23]. So, you have a choice of numbers. We can conclude that if you’ve owned your own home for many years, it is likely that you will have seen a smaller increase in housing costs than a young couple looking for a new apartment in an urban area. That is especially true now in 2022 post-covid.

While there are housing booms and busts, the price level of housing should in the long run rise pretty much in line with the cost of building one, plus the cost of the land. When the price of houses or apartments is above the cost of building a new one, developers will build more until supply and demand balance. But there is a limited supply of land, especially in cities, so the price of land, and along with it the price of housing built on that land, rises. In many locations zoning restricts building multi-family housing, further restricting supply[24].

The United States is hardly an outlier in housing costs. According to OECD data, the US is towards the middle of the pack in terms of housing cost as a fraction of income at around twenty five percent on average[25]. However, “affordability” of housing very much depends on where you live and your income level. New York City dwellers, on average, spend about half their incomes on housing, and lower income people here and in other high-income countries spend a larger share of their already limited incomes on housing, often forty percent or more.

The Future of Services Productivity

The “Services Sector” includes a huge range of activities that are grouped together more by the fact that they aren’t goods-producing rather than any other similarity. What do warehousing and logistics have in common with teaching and legal work? Looking at the future of “services productivity” really requires a detailed analysis of each one.

That said, for some time now we have been hearing about how artificial intelligence (AI) will any day now take over one or another service job. Trucks will be able to drive themselves, AI will write legal documents, and robots will take over the work of home health aides.

All these things may come to pass, but probably more as assistants to humans rather than full replacements at least at first. That will boost productivity in services, but at the same time cause some employment dislocations. Since services are widely distributed, it is unlikely we will see the same kind of regional trauma as has been the case in geographically concentrated manufacturing industries. A bit tongue in cheek, it also seems that services are subject to a form of Parkinson’s Law: they seem to expand as needed to achieve full employment.

In short, I think it is right to be optimistic about the future of services productivity, but we have to keep in mind that firms will only invest in automation when the cost is less than the cost of human labor to do the same job, or to offer a new service. The reading of mammograms by AI, for example, allows radiologists to read more mammograms while also providing a “second opinion”. Humans are still irreplaceable when it comes to interacting with other humans. Japan has tried hard to introduce eldercare robots, but so far without success[26]. We should remember that enhanced productivity increases output per hour worked, so it always increases per capita income. The problem is in distributing the benefits. As with many services, the productivity impact of AI will in some cases be hard to measure. While the number of mammograms accurately read per hour of analyst time is quantifiable, how does an AI used to produce highly tailored sales emails or fake product reviews affect overall productivity?

[1] This is misleading because there has been a huge increase in the use of contract labor by the Federal Government. Brookings estimates the total at around 10 million when such labor is added. See https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-true-size-of-government-is-nearing-a-record-high/.

[2] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.SRV.EMPL.ZS?locations=XD-XT-XM-CN-IN

[3] “The Accuracy of BLS Productivity Measures.” 1999 https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1999/02/art2full.pdf.

[4] Ibid. BLS stands for Bureau of Labor Statistics, BEA for Bureau of Economic Analysis. These two agencies are responsible for most of the US statistics on employment and productivity.

[5] This category is a testament to the difficulty of consistently pricing groups of products over time. The category includes televisions and computers which have seen enormous raw and “quality adjusted” price decreases over the period, which makes the 1960 to 2019 price change almost meaningless.

[6] Operating expenses of private nonprofits such as hospitals and universities. See https://www.bea.gov/help/faq/1009#:~:text=Final%20consumption%20expenditures%20by%20NPISHs,less%20their%20sales%20to%20households.

[7] The overall PCE ratio from 1960 to 2019 is 6.7 compared to the CPI ratio of 8.6.

[8] You may notice that these BLS consumer price indexes are different from the ones shown in the table above which are prices calculated using different methodology by the BEA. In general, the BEA numbers are lower, among other things they recognize that consumers may substitute products or services when prices change, while the BLS with its mandate to track in more or less real time doesn’t have information about consumer spending that would let it make such an adjustment. See “Differences between the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics May 2011 Volume 2, Number 3. https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/archive/differences-between-the-consumer-price-index-and-the-personal-consumption-expenditures-price-index.pdf. The PCE is designed to reflect actual consumer spending.

[9] https://us.milliman.com/en/insight/2021-Milliman-Medical-Index

[10] The prices of individual drugs, weighted for total consumption dollars, haven’t gone up much but we’re consuming a lot more drugs.

[11] Clearly CAT scans weren’t available in 1960, so while prices have gone up, for example for a room, there are many new services being provided as well which results in higher expenditures. The aging population is also a factor.

[12] The per capita cost shown here is higher than personal consumption expenditures because total healthcare spending includes items such as research.

[13] Cronin, Joe. 2020. “Ranking the Top Healthcare Systems by Country.” International Citizens Insurance. April 30, 2020. https://www.internationalinsurance.com/health/systems/.

[14] Himmelstein, David U., Terry Campbell, and Steffie Woolhandler. 2020. “Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada, 2017.” Annals of Internal Medicine 172 (2): 134–42.

[15] “6 Reasons Healthcare Is So Expensive in the U.S.” 2015. Investopedia. August 6, 2015 updated January 2022 6 Reasons Healthcare Is So Expensive in the U.S..

[16] “The-Pharmaceutical-Industry-an-Overview-of-Cpi-Ppi-and-Ipp-Methodology.pdf.” n.d. https://www.bls.gov/ppi/methodology-reports/the-pharmaceutical-industry-an-overview-of-cpi-ppi-and-ipp-methodology.pdf.

[17] The same can be said of academic paper publishing, but fortunately there is a fascinating free article on the pricing of insulin in the US in 2020, prior to Biden’s reducing the price https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/7/1/lsaa061/5918811.

[18] Center for Drug Evaluation, and Research. n.d. “Generic Competition and Drug Prices.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/generic-competition-and-drug-prices.

[19] There are other reasons. For example, the healthcare industry lobby is the largest by far in the US. See https://www.statista.com/statistics/257364/top-lobbying-industries-in-the-us/.

[20] Rassier, Dylan G., Bettina H. Aten, Eric B. Figueroa, Solomon Kublashvili, Brian J. Smith, and Jack York. n.d. “Improved Measures of Housing Services for the U.S. Economic Accounts.” BEA. Accessed May 1, 2022. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/2021/05-may/0521-housing-services.htm.

[21] 89% of the population lives in “urban” areas.

[22] “Shelter” is a major component of the CPI-U, so the relative increase in shelter costs would be even higher if this component were excluded.

[23] US Census Bureau. n.d. “Historical Census of Housing Tables: Gross Rents.” Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/coh-grossrents.html. Gross rent is the monthly amount of rent plus the estimated average monthly cost of utilities (electricity, gas, water and sewer) and fuels (oil, coal, kerosene, wood, etc.).

[24] Zoning is of course a government (usually local) distortion of the free market. Without zoning, one could build a high-rise apartment building in an upscale single-family community, and that might very well be the optimal use of the land in simple free market terms.

[25] For the US the OECD report uses gross income, while for most other countries it uses disposable. See HC1.2. HOUSING COSTS OVER INCOME at https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC1-2-Housing-costs-over-income.pdf

[26] Wright, J. (2023, January 9). Inside Japan’s long experiment in automating elder care. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/01/09/1065135/japan-automating-eldercare-robots/.

[RF1]Note that calculation of GDP includes imputed values (see ChatGPT generated synopsis). Clearly the same problem of valuation will apply to both productivity and GDP calculation. ATM services are a imputed consumption value. In the section on how productivity is measured, I should mention imputed values. See https://www.bea.gov/help/faq/488 “Free” digital media (Facebook) contribution to GDP is included through advertising revenue although some feel there should be an additional imputed value. See ChaptGPT synopsis and https://www.bea.gov/research/papers/2017/measuring-free-digital-economy-within-gdp-and-productivity-accounts