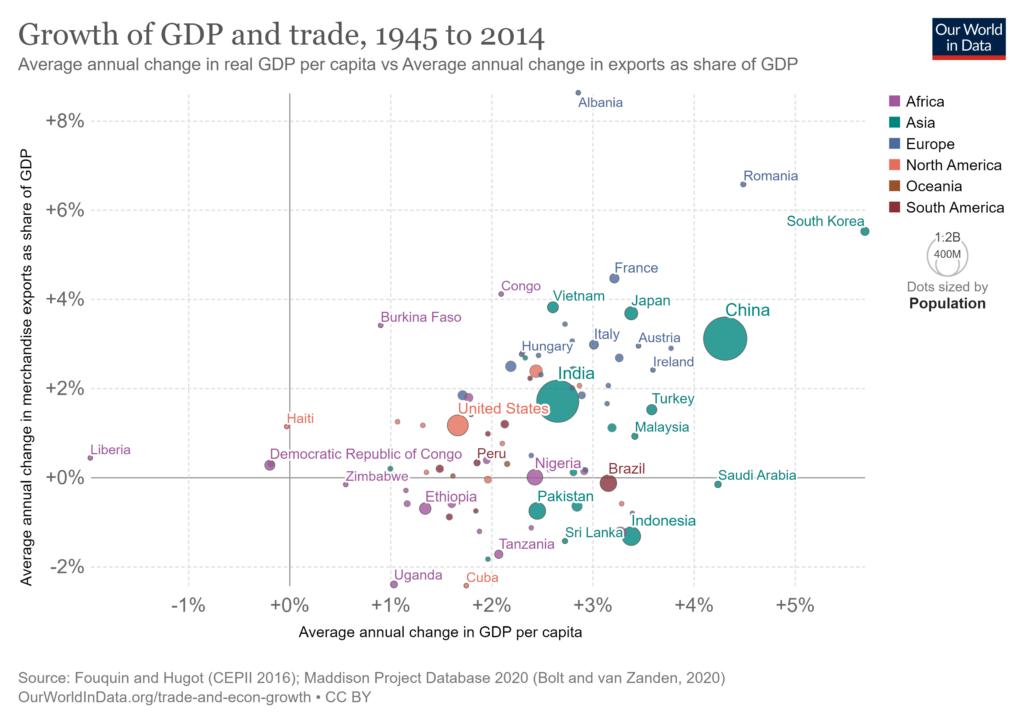

The above discussion focused on trade in advanced economies, what about developing ones? The general benefits of trade apply to any country, rich or poor. Trade allows countries to increase their productivity by focusing on areas where they have a comparative advantage. This helps explain the observed correlation between freer trade and an increased rate of productivity growth in developing countries. A 2003 study found that over the 1950–98 period, countries that liberalized their trade policies experienced average annual growth rates that were about 1.5 percentage points higher than before liberalization. This is a large increase given that a “good” growth rate is around 3%. After trade liberalization, investment rates rose 1.5 to 2.0 percentage points, supporting the idea that increased trade fosters growth in part through physical capital accumulation[1]. We have already noted the studies relating economic growth to trade volume, but this chart from “Our World in Data” provides a visual representation of this relationship[2].

Figure 33: GDP per capita vs growth in trade Source: https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-econ-growth.

This chart shows correlation not causation, increasing wealth can lead to increased trade or the other way around. Since countries differ in so many ways, it is hard to draw statistical conclusions about the relationship between trade and development, but in the World Bank study “Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers, and Policies” we cited in the section on productivity convergence, a number of country case studies found that export promotion, global value chain integration, and foreign direct investment (FDI) were important in transitioning to higher-productivity growth and development. These are all trade related. In our brief case study of China, trade and FDI were key factors in providing funding for development, and other initially poor countries have taken the same path.

Increasing trade is often cited as a major factor in lifting people out of extreme poverty and expanding the middle class in developing countries. It can also have a positive effect on inequality. A study of 27 countries with advanced economies and 13 developing countries finds that shutting off trade would deprive the richest of 28 percent of their purchasing power, but the poorest would lose 63 percent because they buy relatively more imported goods[3]. Studies of some countries have shown that exporting firms tend to hire more women (not surprising when the export is clothing and textiles) which leads to greater economic empowerment for women.

There can be negative effects from trade in developing countries as well. As usual, those employed in trade competitive industries can suffer. In developing countries, agriculture often faces trade competition, and inefficient farmers may find themselves underpriced by imports. Countries that specialize in exporting commodities are subject to the volatility of commodity prices. In fact, any country which depends on exporting a limited number of products is subject to market swings. And the benefits of trade are highly dependent on how a country is governed. If the profits of trade are skimmed off for the enrichment of a few rather than being reinvested and passed along as higher wages, growth will be stymied.

Despite the varied paths to growth taken by different countries, trade is generally seen as an important spur to economic growth by leading to a virtuous cycle of specialization, capital accumulation, technology transfer, and increased productivity and higher incomes. Higher incomes in turn lead to better health, higher levels of education, improvements in productivity and increased domestic demand. This is in addition to the lower costs and greater selection that are usual benefits of trade.

[1] Wacziarg, Romain, and Karen Horn Welch. “Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence.” The World Bank Economic Review, November. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1093/wber/lhn007. This is actually a 2003 NBER paper http://www.nber.org/papers/w10152 The analysis shows considerable variance in results between different countries and when the trade liberalization took place.

[2] https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-econ-growth.

[3] Fajgelbaum, Pablo D., and Amit K. Khandelwal. 2014. “Measuring the Unequal Gains from Trade.” Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20331.