Benefits of Trade

Trade has enormous potential economic benefits as we showed in the primer, regardless of whether it is within a country or between two countries (bilateral trade). Those benefits come in the form of lower prices, greater overall productivity, and an increased selection of goods and services. Without trade, there wouldn’t be bananas available in Pittsburgh and iPhones and televisions would cost much more. Trade is in fact what brings us the advantages of free markets: “optimal” resource utilization under the constant balancing of supply and demand and the drive to productivity under the pressures of competition. However, trade can, and does, create winners and losers. While in economic theory, the winners could compensate the losers and still come out ahead, in practice workers will suffer if competition costs them their job, whether that competition is from Huntsville, Alabama or Hunan, China. In short, the benefits of trade, such as lower prices and greater selection, are widespread, while the pain is borne by those displaced by trade competition. The box below shows how trade can cost jobs but benefits consumers through lower prices and selection.

| Prices Versus Jobs “In 1960, an average American household spent over 10 percent of its income on clothing and shoes – equivalent to roughly $4,000 today. The average person bought fewer than 25 garments each year. And about 95 percent of those clothes were made in the United States. Fast forward half a century. Today, the average American household spends less than 3.5 percent of its budget on clothing and shoes – under $1,800. Yet, we buy more clothing than ever before: nearly 20 billion garments a year, close to 70 pieces of clothing per person, or more than one clothing purchase per week. Oh, and guess how much of that is made in the U.S.: about 2 percent.” From Article “Why America Stopped Making Its Own Clothes” by Stephanie Vatz May 24, 2013, on WQED. https://www.kqed.org/lowdown/7939/madeinamerica |

Because of the distributed nature of the benefits of trade, and the difficulty of separating out other factors, such as productivity increases, calculating those benefits is subject to a high degree of uncertainty. Nonetheless economists have undertaken a number of studies to attempt to do just that. If we remember that GDP per capita is a measure of average income in a country, the question can be asked “does increased trade raise GDP per capita”. Below we look at two such studies which also provide a glimpse into how economists try to answer such questions. You can skip the next couple of paragraphs if you don’t want the details.

One of the often-quoted studies of the benefits of trade, “Does Trade Cause Growth?”[1] looked for a relationship between how close countries are to each other and their per capita GDP. Why physical proximity? Looking directly for a relationship between per capita GDP and the volume of trade as a percent of GDP has the problem that one can’t be sure whether high GDP per person causes a high level of trade per person or vice versa. However, as we saw earlier, countries do most of their trading with neighboring or close by countries, so trade volume can be predicted based on how close countries are to each other, and a few other factors such as the size and population of the countries. The important point is that it seems unlikely that GDP per person will depend on how close countries are to each other except through this trade effect. If countries with less trade as measured through this proxy have lower GDP per capita than countries with more trade, it indicates that it is trade that explains the increase in GDP, not the other way around.

The authors first looked at how well their physical proximity (and size) measure correlated with actual trade volumes as a percent of GDP and they found a strong positive (and highly significant) correlation, not surprisingly – the closer countries are to each other the more they trade for the most part. They then used the proximity measure to look for a correlation with per capita GDP. They found a strongly positive correlation indicating that indeed increased trade volume “explains” higher GDP when all other factors stay the same. Below are the author’s conclusions based on their statistical analysis:

The results of the experiment are consistent across the samples and specifications we con- sider: trade raises income. The relation between the geographic component of trade and income suggests that a rise of one percentage point in the ratio of trade to GDP increases income per person by at least one-half percent. Trade appears to raise income by spurring the accumulation of physical and human capital and by increasing output for given levels of capital.

The results also suggest that within-country trade raises income. Controlling for international trade, countries that are larger – and that therefore have more opportunities for trade within their borders – have higher incomes. The point estimates suggest that increasing a country’s size and area by one percent raises income by one-tenth of a percent or more. And the estimates suggest that within-country trade, like international trade, raises income both through capital accumulation and through income for given levels of capital.

Unfortunately, as the authors note, there is a pretty wide envelope of statistical uncertainty about the result, which is typical of all the studies that try to isolate the overall effects of trade.

While some studies, such as the one above, try to correlate trade with changes in GDP statistically, others use elaborate models (think weather forecasting) in which various scenarios can be computed to predict how the economy would respond to more or less trade and different trade policies. The results of those models can then be used to compute the contribution of trade to GDP.

While the computed addition to GDP for these studies varies widely, they all show an increase in overall wealth resulting from an increase in trade, including those studies that look specifically at advanced economies such as the United States or Europe.

A review of several of these “econometric” studies of the possible size of the net economic benefits of trade to the US is given in a 2015 Peterson Institute for International Economics post which concludes:

increased trade between 1988 and 2008 provided an estimated $720 billion boost to the US 2008 GDP. However, over that same time period, competition from imports and outsourcing suppressed US wages to the tune of $140 billion[2]

The estimated $720 billion boost is an ongoing per year addition to overall wealth (i.e. GDP) and includes the benefit of lower prices, both directly from imports but also from increased productivity in the US as companies compete against imports. The report goes on to estimate that from 1988 to 2008, “average annual wages received a boost of over $2,000 per worker owing to expanded trade. After subtracting the losses due to increased competition, the net average boost in wages was about $1,000 per worker.” Using a statistical household size of 2.5, that translates to a net annual income increase of $2,500 per family from 1988 to 2008. Over the longer period of 1950 to 2015 the per household net benefit of trade has been estimated at $18,000[3] although “what ifs” over such a long period of time are highly uncertain.

This of course is an average number. How were these gains distributed? Again, without looking only at workers directly affected by trade, the authors find that the less well-off benefited most from the relatively lower prices brought by trade (as well as productivity increases of course). That’s because poorer households spend proportionately more on goods than services than wealthier households, and goods prices are much more affected by trade[4]. On the other hand, if one considers that lower income workers’ wages were more impacted by trade than wealthier workers and that wealthier people earned more from trade related corporate profits and income, the net effect of trade was to increase income inequality somewhat. To quote the already mentioned paper, which uses some simplifying assumptions:

Richer households did enjoy a disproportionate share of benefits from globalization, because of their dominant claim on corporate profits and proprietors’ incomes and the very small impact of foreign competition on the wages of highly skilled workers. Even so, the globalization boom cannot explain 90 percent of the rise, between 1988 and 2008, in the share of household income captured by the top 20 percent[5].

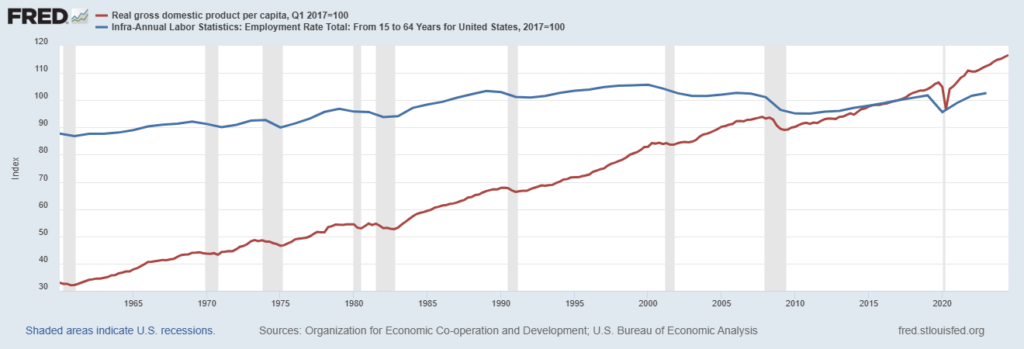

We often overlook the benefits of globalization (i.e. freer international trade and financial flows), because they show up as lower costs, primarily for manufactured goods. But as the studies above suggest, considering the country as a whole, international trade is, on net, a substantial net economic plus to the economy. The chart below shows that the rise of trade in the US, as in most other advanced economies, has actually coincided with an extended period of high employment (blue line below) and continued per capita GDP growth (red line) as many authors have pointed out. It is easy to see the effects of the recessions, but impossible to pick out the trade “shocks”, or large increases in trade, which occurred since 1995.

Figure 31: Employment Rate (index, blue) and GDP per capita real growth (index, red). Recessions shaded in gray. Source: BEA, OECD via FED. Indexes don’t show actual values but rather show how values change over time.

Costs of Trade

So, if international trade is beneficial for advanced economies, why has it been a contentious issue in some advanced economies, and in particular the US?

The answer is that the costs of trade, primarily employment dislocations, are much easier to see than the benefits (unless you’re involved in the huge export sector) and can be concentrated geographically. Additionally, trade probably gets the blame for “job losses” that are really caused by the large increases in manufacturing productivity we noted earlier, and industry movement within the country itself. Studies of the “costs of trade” try to tease out the trade specific job dislocations from these confounding factors. Before we look at the studies themselves, let’s consider these confounding factors.

First, we need to note that nobody blames trade for the huge decline in agricultural employment in the US or other advanced countries. Clearly greater productivity is responsible for these declines, since we run a small surplus in agricultural trade and produce more now than ever before[6]. There can be no doubt that agricultural productivity gains have forced farm families to seek alternate employment and depopulated rural areas, but nobody blames these job losses on trade. The same is largely true of manufactured goods: productivity increases explain most of the job dislocations and losses in that sector as we’ll see in the section below on trade and manufacturing.

As noted, the great increase in trade over the last 30 years or so, largely involved manufactured goods, and in particular manufactured goods from low wage countries, and even more particularly the huge increase in manufactured imports from China. A massive change in trade like this is called a “shock” by economists, since it represents a departure from the long-term trend. In a 2016 paper, David Autor and his coauthors, survey the economic literature (including their own papers) that seeks to identify the impact of this shock on workers in the US and other advanced economies[7]. They conclude that:

Alongside the heralded consumer benefits of expanded trade are substantial adjustment costs and distributional consequences. These impacts are most visible in the local labor markets in which the industries exposed to foreign competition are concentrated. Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences.[8]

It should be noted that the “China shock” was a onetime event that greatly expanded the trade between the advanced economies and a low wage economy. The adjustment to that shock in terms of what is made where is mostly complete, however the authors conclude that the negative impacts on affected workers and, to a lesser extent regions, dissipated only slowly.

What were these impacts? In a 2013 paper, the authors divided the US into “commuting zones” in which workers are clustered[9]. They then compute how “exposed” the businesses in these commuting zones were to competition from Chinese imports. This lets the authors see how the level of import exposure correlates with wages, employment, and transfer payments such as unemployment and disability insurance. They find that between 1992 and 2007 manufacturing employment job losses in highly exposed commuting zones are not balanced by gains in other local employment and instead lead to greater unemployment, and workers dropping out of the workforce, including through increased permanent disability claims. Meanwhile wages are negatively impacted generally within the commuting zone, mostly in non-manufacturing jobs for which displaced workers compete. To quote:

Despite the responsiveness of local transfer payments to local import exposure, on the whole there appears to be limited regional redistribution of trade gains from winners to losers. Comparing again the residents of [commuting zones] at the 75th and 25th percentile of import exposure, those in the more exposed location experience a reduction in annual household wage and salary income per adult of $549, whereas per capita transfer income rises by approximately $58, thereby offsetting just a small portion of the earnings loss[10].

“Transfer income” refers to Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) and unemployment payments which are short term, and disability insurance (SSDI) and other public assistance. Basic economic theory often assumes for simplicity that workers migrate freely around a country, thus equalizing wages, but labor migration has actually substantially slowed in recent decades, as this result indicates. Some economists cite transfer payments as a partial possible cause of lower mobility: some people don’t leave areas negatively affected by trade or lower demand for agricultural workers because of transfer payments.

As to how the China trade related effects are distributed between higher and lower wage workers, the paper concludes:

Although trade shocks disrupt the careers of both high-wage and low-wage individuals, there is also substantial heterogeneity in patterns of adjustment. Workers whose pre-period wage falls in the top earnings tercile of their birth cohort react to the trade exposure of their initial firm primarily by relocating to firms outside the manufacturing sector. They do not experience an earnings loss relative to their peers who started out in less trade-exposed industries. By contrast, workers in the bottom tercile of pre-period earnings relocate primarily within the manufacturing sector, and often remain in industries that are hit by subsequent increases in import competition. These low-wage workers suffer large differential earnings losses, as they obtain lower earnings per year both while working at the initial firm and after relocating to new employers.[11]

Similar results were found in studies of the effects of the China trade in Norway and Spain,

and in an earlier study on the effects of NAFTA. In the latter, high school dropouts in formerly “protected” (i.e. protected by tariffs) industries, had wage growth that lagged 17 percent behind similar workers in industries that had not been formerly protected[12].

Finally, the 2016 survey paper mentions a National Bureau of Economic Research study that uses a computer model to quantify the “welfare effects” of the China shock.[13] In economics, overall “welfare” is not the simple addition in dollars of how much each person gains and loses from trade, it considers the relative importance of such gains and losses to each person. So, when a low wage person loses $1,000 of income, they have lost more “welfare” than a person who is better off gets from an extra $1,000 of income. This model implicitly includes factors such as the costs to a worker of moving to a different locality. The model calculates that the China shock initially produced very little if any overall welfare benefit or loss to US families but delivered a strong positive welfare benefit across all states in the long run. Given the weighting that “welfare” calculation gives to the losses to workers in affected industries, this indicates an even larger purely dollar gain from increased trade. By the way, this model has some other interesting results. Which state do you think had the largest initial job losses from increased trade with China? It was California followed by Texas! Why? The computer and electronics, and furniture industries each contributed about 25% of the China shock related decline in manufacturing employment, followed by the metal and textiles industries. California and Texas had large computer and electronics sectors, which were heavily impacted by Chinese imports. These are hardly the first states that come to mind when one thinks of depressed US regions, and indeed both states eventually benefited from China trade as much as other states.

Finally, to put trade shock employment dislocations in context, every year in the US, since 2003, there have been about 29 million jobs lost and 30 million gained[14]. Manufacturing, which has borne the brunt of dislocations due to trade shocks, has lost an average of about 2 million jobs annually and gained 1.85 million for a net loss of about 123,000 annually. As we will see shortly about 20% of the job losses in manufacturing over the period can be attributed to trade shocks. Churn is normal and widespread in employment as firms come and go, automation proceeds, and companies move around the country and the world.

To sum up, we’ve seen that international trade has a large net positive overall impact on US and other advanced economies, but that trade shocks have caused job dislocations that harm affected workers and regions.

Loss of Manufacturing Jobs – “Deindustrialization” – and Trade

In the section on the productivity frontier, we saw that the enormous shift in employment from manufacturing to services could mostly be explained by higher labor productivity increases in manufacturing. However, we noted that trade could explain part of the decline, with a third factor being a relative decline in demand for manufactured goods. Indeed, trade is often mentioned as a major contributing factor in the relative decline of manufacturing employment in advanced economies such as the US.

A brief review of theory can help put trade-related manufacturing job dislocations into context. In balanced trade between a high productivity, high wage, country and another such country one would expect gradual specialization and little job dislocation when trade barriers are lowered. This is largely what is observed. On the other hand, in balanced trade between a high productivity/wage country and a low wage country, one would expect the high wage country to export capital intensive goods and high value services and import labor intensive goods and services. A trade “shock” that increases trade between a high wage country and a low wage country will displace workers from labor intensive, lower wage, jobs and increase employment in higher wage higher productivity jobs. This is pretty common sense and is what is observed: trade with low wage countries essentially wiped out the US domestic clothing industry. One would expect such trade to require fewer workers since, due to higher labor productivity, the exported goods will require less labor per dollar of output than was required in the old labor-intensive industries. Since trade is still largely in manufactured goods, the effect will be to reduce manufacturing employment in the high-income country, even with balanced trade. Of course, overall productivity and total income will go up in the long run in both countries as a new trade equilibrium is reached. We should note that opening up to trade is largely a one-time occurrence in the modern world with low transportation costs. “Shocks” only occur when there is a drastic change in barriers to trade[15]. Once barriers have been reduced, trade patterns evolve over time between countries much as they do internally within a large country or trading block such as the European Union. Clothing manufacturing is a major industry now in the low wage countries of Vietnam and Bangladesh, and less important to China, but that drift has had no impact on US domestic employment which has already adapted to low-cost clothing imports.

In sum, when trade is balanced and trade shocks have worked their way through the economy, overall productivity and total income will be higher than in the absence of trade, but trade shocks will have caused job displacements and lower overall manufacturing employment.

Trade deficits also affect the mix of jobs, and manufacturing in particular. Since manufactured goods are the largest component of trade, a shortfall in exports means that fewer manufacturing jobs will be created in the export sector than would be the case with balanced trade. A trade deficit is thus sometimes said to have “employment content” but since we have full employment now in 2023 that really translates not to lost jobs, but fewer manufacturing jobs compared to service jobs. Unlike trade shocks, a trade deficit will continue to suppress manufacturing employment as long as it continues.

So much for the theory. What does the data say about the relationship between trade and manufacturing employment declines and dislocations?

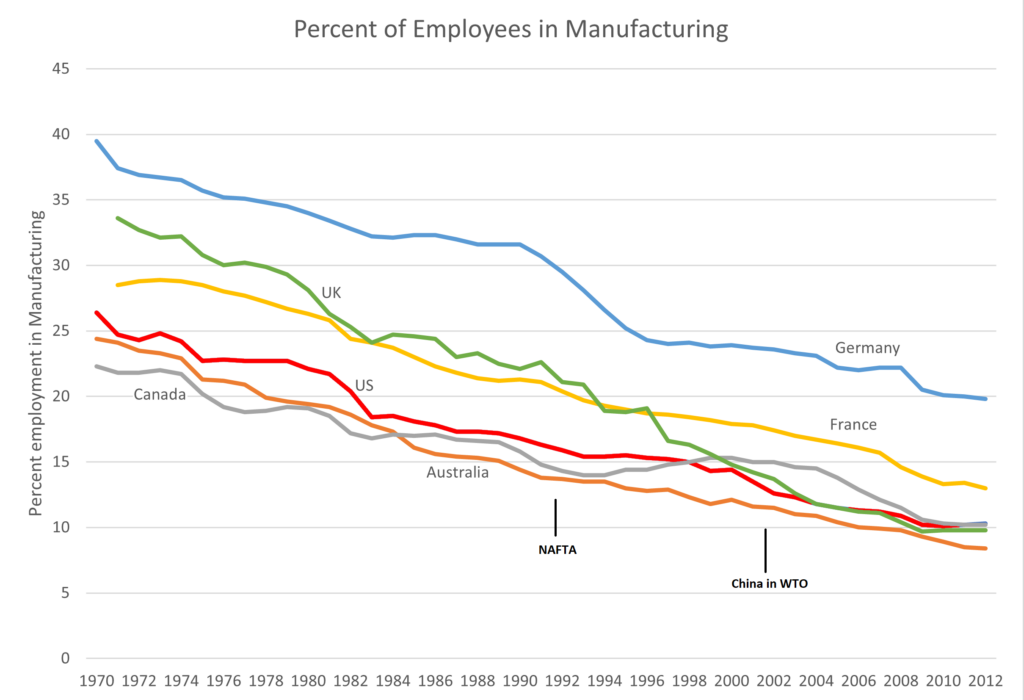

As we saw in the section on the productivity frontier, all the high wage countries have seen declines in manufacturing employment as a percentage of total employment, even when, like Germany, they run substantial trade surpluses. As the chart below from that section shows, there is no perceptible change in the downward slope of US manufacturing employment declines as a result of either NAFTA or the “China shock”. While this is hardly scientific, it does suggest that manufacturing jobs lost to increased trade in labor intensive industries were largely offset by increased manufacturing employment elsewhere and that the decline has more to do with labor productivity increases.

Figure 32: Figure: Percent of employees in manufacturing, some rich countries. The dates of a couple of trade agreements are shown. Source: International Comparisons of Annual Labor Force Statistics, 1970-2012 Bureau of Labor Statistics

Above we discussed a study of the local effects of the “China shock” within commuting zones. Applying this econometric analysis to manufacturing as a whole, the study finds that between 1990 and 2007, 21% of manufacturing job losses could be attributable to the China trade shock[16]. Which means that 80% of manufacturing job losses during the period have other explanations, and as we’ve seen, the rapid growth of labor productivity in manufacturing as in agriculture provides that explanation… mostly. In the special case of the US, it is important to note that the trade deficit ballooned during this period as consumers gorged on inexpensive imported goods and businesses sourced components from overseas. If trade had been balanced, manufacturing jobs would have been created that would have helped balance out the job losses. The manufacturing “employment content” of the trade deficit has been estimated as 1.65 million full-time equivalent jobs in 1990, rising to 3.3 million jobs in 2000 and staying roughly at that level through 2010[17]. The fraction of the workforce in manufacturing would have declined due to productivity increases as it has in wealthy countries running trade surpluses, but the US has lost more manufacturing because of its increased trade deficit. A final contributor to “deindustrialization” is simply saturation. While people buy more manufactured goods, these goods cost less, and overall people now spend more of their incomes on services than they used to[18].

Adding it all up, in the absence of trade shocks, manufacturing employment as a share of total employment has fallen because of greater labor productivity gains in manufacturing than services. The dollar output of manufacturing as a fraction of GDP in the US has hardly changed at all despite this decline in relative employment, once again indicating the importance of productivity growth[19]. The rapid increases in trade enabled by lower transportation costs, better logistics, lowered tariffs, financial flows, and the rapid expansion of manufacturing in low wage countries caused many to lose manufacturing jobs in affected industries in wealthy countries, but these job losses were largely offset by increased employment in export manufacturing in countries with balanced trade. In the US, closing the ongoing trade deficit would boost manufacturing employment perhaps by 3 million jobs which is a sizeable when measured against current manufacturing employment of 12 million[20]. Closing a trade deficit is easier said than done.

[1] Frankel, Jeffrey A., and David H. Romer. 1999. “Does Trade Cause Growth?” The American Economic Review 89 (3): 379–99.

[2] “Does Foreign Trade and Investment Reduce Average US Wages and Increase Inequality? (Part 2).” 2015. PIIE. November 10, 2015. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-investment-policy-watch/does-foreign-trade-and-investment-reduce-average-us-wages-and.

[3] Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Zhiyao (Lucy) Lu. 2017. “The Payoff to America from Globalization: A Fresh Look with a Focus on Costs to Workers (Brief 17-16).” Peterson Institute for International Economics, May. https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/pb17-16.pdf. Quoted by the US Chamber of Commerce.

[4] Fajgelbaum, Pablo D., and Amit K. Khandelwal. 2014. “Measuring the Unequal Gains from Trade.” Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20331.

[5] “Does Foreign Trade and Investment Reduce Average US Wages and Increase Inequality? (Part 2).” 2015. PIIE. November 10, 2015. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-investment-policy-watch/does-foreign-trade-and-investment-reduce-average-us-wages-and.

[6] The EU nations substantially subsidize their agriculture, as does the US.

[7] Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2016. “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade.” Annual Review of Economics 8 (1): 205–40.

[8] Autor et al, p 205

[9] Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” The American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68.

[10] Autor et al 2016, p231

[11] Autor et al 2016, p233

[12] McLaren J, Hakobyan S. 2016. Looking for local labor market effects of NAFTA. Rev. Econ. Stat as summarized in the Autor 2016 paper.

[13] Caliendo, Lorenzo, Maximiliano Dvorkin, and Fernando Parro. 2015. “The Impact of Trade on Labor Market Dynamics.” Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21149. Note that working papers are not peer reviewed.

[14] These are private, non-farm, averages for the period from 2003-2023 from https://www.bls.gov/charts/business-employment-dynamics/gross-job-gains-gross-job-losses-industry.htm.

[15] In addition to tariffs and transportation costs, shocks can include price fixing ala OPEC, natural disasters such as Covid, wars, and economic trade sanctions.

[16] Autor et al 2013, page 2,140. Acemoglu et al. (2016) find 10% direct and another 10% indirect losses, so similar results.

[17] Lawrence, Rising Tide, 2013 p 101.

[18] Lawrence 2013 p 95

[19] See chart in Baily et al 2014 p 4.

[20] Recent US trade deficits have been around $800 billion. Using a rough rule of thumb of 5,000 jobs per billion dollars in manufacturing, closing the trade deficit would result in 4 million jobs. This is an upper limit: it assumes trade would be balanced entirely through manufacturing. The mix also matters, only about 3,000 jobs are created per billion dollars in high tech.

[RF1]Redo as my own chart