Population Growth and “Peak Human”

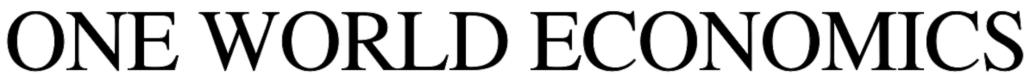

The chart below shows how the earth’s human population has taken off on a logarithmic climb since about 1900, not much more than 100 years ago. The industrial and agricultural revolutions along with advances in medicine allowed cities to grow and absorb an ever-larger population. As discussed earlier, 80% of the population of most countries was engaged in agriculture in the 1700’s, which meant that populations were constrained by the amount of farmable land. The mechanization of agriculture and improvements in crop yields along with the availability of highly productive industrial jobs set the stage for this rapid growth which occurred at different rates around the world, and in fact is still continuing.

Figure 69: World and Regional Population Growth. Graphic Source: Our World in Data. WW169

The explosion in world population has been accompanied by huge increases in consumption per person, although this varies widely between countries and regions depending on GDP. The combination of an enormous human population and increasing personal consumption is unsustainable in its current form as we have reached or exceeded the capacity of the earth to supply some of our demands and dispose of our waste.

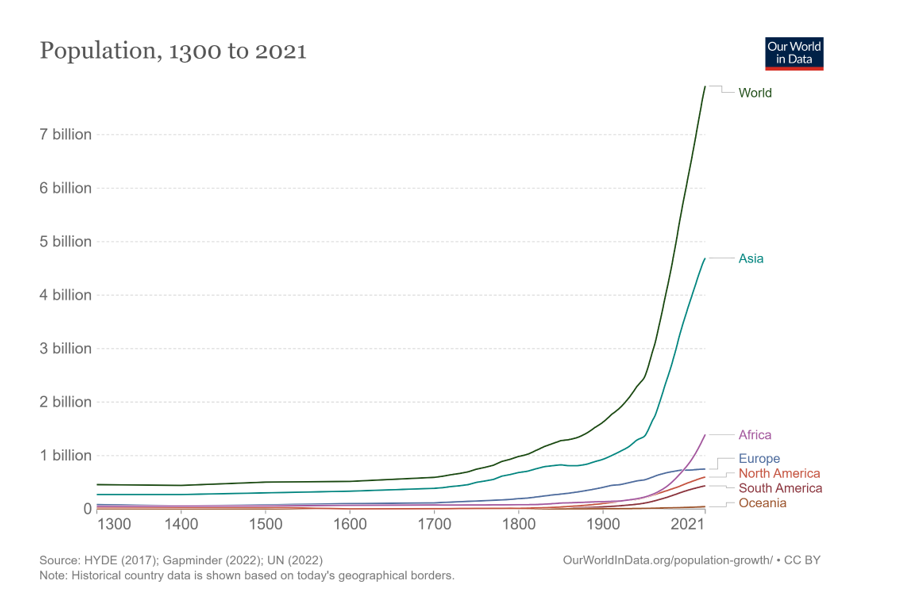

There is some good news on the population front. As noted earlier, fertility rates, or the number of children born per woman on average, have been falling for years[1].

Figure 70: Fertility rates by income group. The approximate world-wide replacement rate is 2.3 children per woman. In advanced economies, the replacement rate is about 2.1 births per woman because of lower mortality rates. Data Source: World Bank CC By

As countries get richer and more urbanized and infant mortality rates fall, the fertility rate goes down. Worldwide, we’re close to the rate that just replaces the current population once the age profile has stabilized. There is a lag between fertility rate decline and that decline being reflected in population numbers because, to put it simply, young people have kids and older people don’t and it takes a while for the young to grow old, and the old to die.

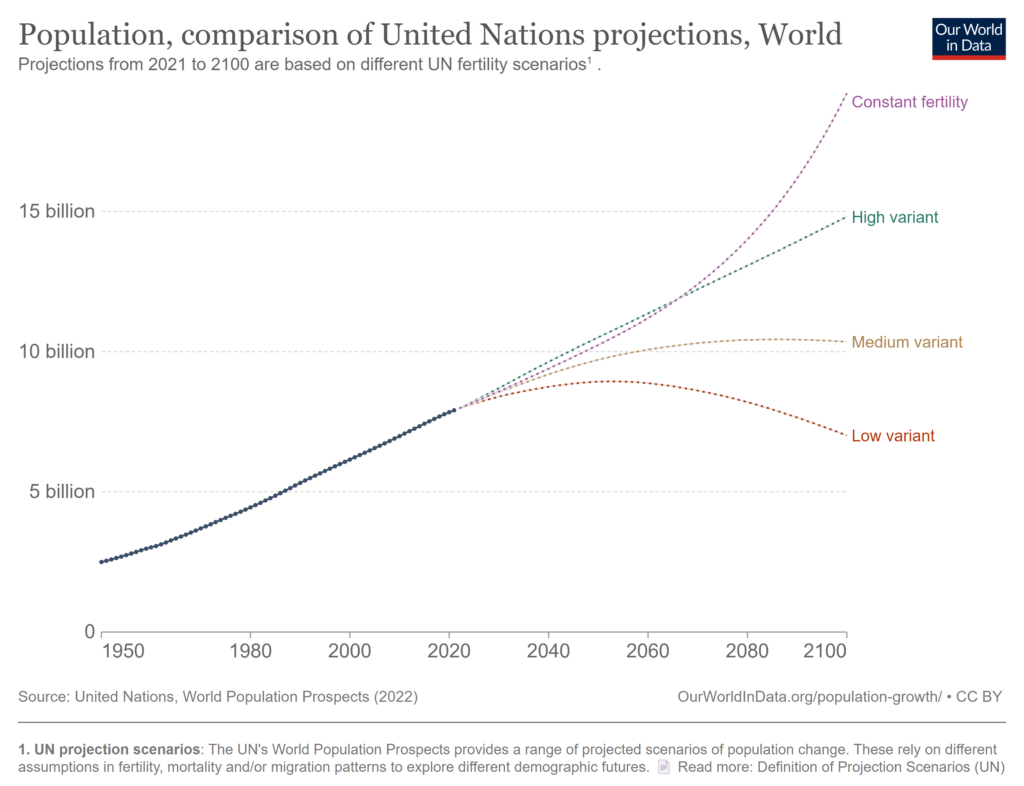

Given predictions about birth rates in the future – which largely depend on rates of economic development and urbanization – along with the dynamics of an aging population, it is possible to estimate the future of the earth’s human population.

Figure 71: UN Human population projections. Source: Our World in Data chart of UN Data CC-BY WW114

Under the medium assumptions, “peak human” population will stabilize at around 10 billion people in 2050, up from the current 8 billion[2]. While the end of population growth is welcome, 10.2 billion is still an increase of 2.2 billion people in 30 years, or about 28% more people than the earth holds now. In other words, we’ll need 28% more food, and other basic necessities at a minimum, not accounting for per capita consumption growth.

Consumption Growth

With some luck, the human population of the world will only grow by another 28% or so before reaching “peak human” and then perhaps slowly declining. However, as people earn more, they consume more, and that will increase demand for already strained resources. We’ll get into what those strained resources are in more detail later, but what can we say about increases in demand?

As people’s incomes increase, they want to eat “better” which usually means consuming more meat and fish and less grain. They improve their housing and buy consumer goods and household appliances. They switch from bicycles to motor scooters to cars. They buy air conditioners and heat their houses. There is also an increase in demand for services such as better education and healthcare, entertainment, and restaurant meals which don’t require a lot in the way of natural resources.

One way of gauging the potential impact of consumption growth is by estimating what it would take in natural resources if the current 8 billion people on earth consumed as much as those in rich countries. For example, in many better off countries there are 6 or more cars for every 10 people[3]. That level of car ownership would require about 5 billion cars worldwide. Currently there are 1.5 billion, so there is potentially demand for at least another 3.5 billion cars. Is that possible? The answer is yes, and no. There is plenty of iron ore for making steel (70% of steel is recycled, but that many cars would require a lot of new steel), and over time the world could pretty easily add the capacity to manufacture that many cars. The limiting factor is actually producing and consuming energy sustainably, both in manufacturing the cars and in running them. Steel manufacture uses a lot of fossil fuels, and running cars, even electric ones, requires a lot of energy. We cannot sustainably manufacture and drive cars without addressing the greenhouse gas problem.

As this example of cars indicates, meeting future world demands without exceeding the sustainable capacity of the earth involves mostly a few fundamental resources. Chief among these is the problem of producing the energy and food we want sustainably, meaning, as defined above, without exceeding the ability of the world to supply our demands or absorb our waste on an ongoing basis.

[1] See the section on “Immigration and the Aging Workforce in the US” in the section on migration.

[2] The assumptions are detailed at https://population.un.org/wpp/DefinitionOfProjectionScenarios/#:~:text=The%20five%20fertility%20scenarios%20are,and%20instant%2Dreplacement%2Dfertility.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_vehicles_per_capita