Worldwide, migrants fall into 3 broad categories: refugees, emigrants, and overseas workers. To repeat the numbers, in 2020 there were about 281 million migrants, meaning people living in a country other than the one they were born in, which represented about 3.6% of the world’s population. Of these about 80 million had emigrated, 169 were overseas workers, and 32 million were international refugees. We will look at refugees first.

Refugees

While refugees receive a lot of news coverage given the direness of their plight, “only” about 12% of migrants, or around 32.5 million people in 2022, were refugees forced from their native countries by disasters and wars. Another 53.2 million people are currently displaced within their country of birth[1]. Most refugees, internal or external, flee their homes because of wars and civil conflicts. More than 8 million Ukrainian refugees have flooded into Europe since the invasion by Russia, with another 5 million displaced within the country[2]. The Syrian civil war has sent 6.6 million refugees over the border with another 6.6 million displaced internally. There are also millions of refugees from wars in South Sudan (2.4 million) and Afghanistan (2.8 million) and from economic disaster in Venezuela (5.6 million). And of course, there are refugees from floods, droughts, earthquakes, and other natural disasters.

Turkey, which borders Syria, currently has the largest share of refugees in the world, with 3.6 million Syrians spread among many, mostly urban, host communities and some refugee camps[3]. Other countries hosting large refugee populations include Colombia with 2.5 million, Germany with 2.2 million, Pakistan with 1.5 million and Uganda with 1.5 million. The US currently has a total of 0.3 million refugees accepted over recent decades[4].

When one thinks of refugees or internally displaced people, the first thing that comes to mind is a refugee camp with rows of tents or chanties. But 92% of internal displaced people live with host families[5] and only about 22% of international refugees live in camps[6]. The large majority of refugees live in urban areas and in many ways resemble economic migrants except that they are more apt to settle closer to home whereas economic migrants, while also looking to minimize distance, mostly settle in high income countries. Sixty nine percent of refugees are hosted in neighboring countries, three quarters in low- and middle-income ones[7], in contrast to economic migrants, most of whom (66%) settle in high income countries.

Given this distribution, the economic impact of refugees on the receiving country is similar to that of economic migrants.

Economic Migrants

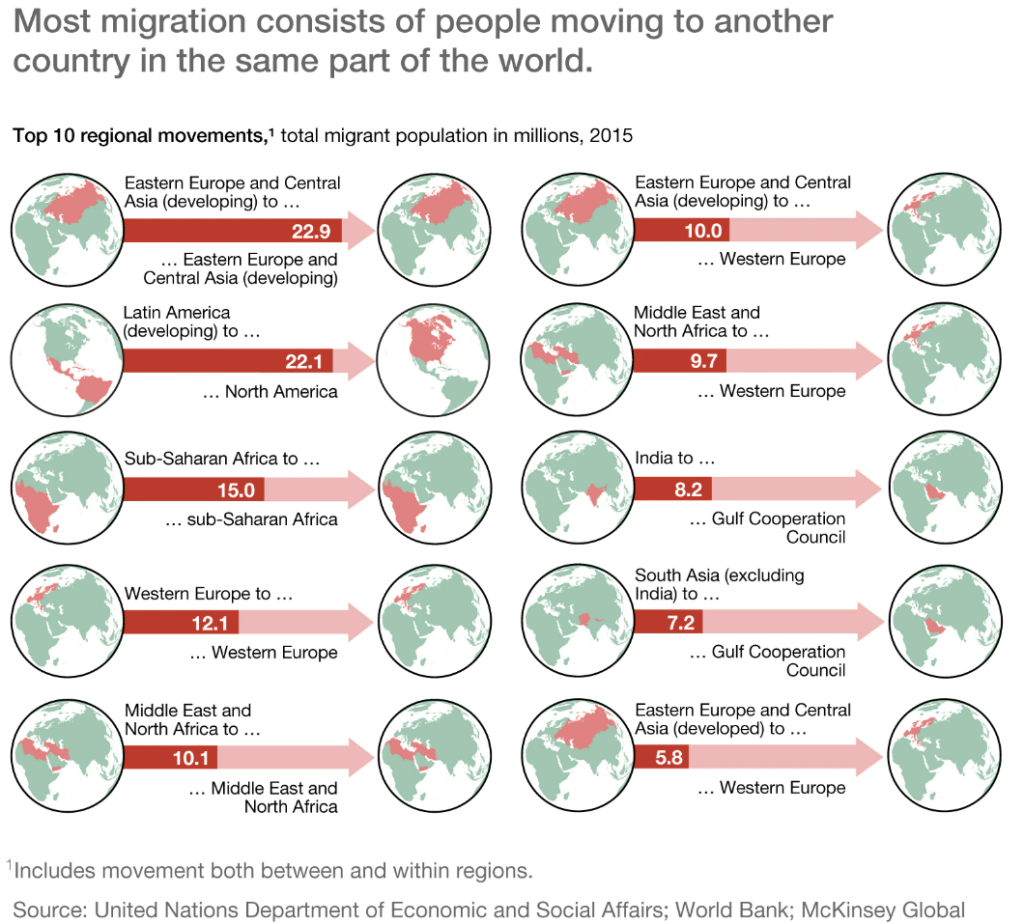

The large bulk of international migrants are considered to have moved for economic reasons. Most such economic migrants go to nearby countries or regions as this chart from a McKinsey Report shows.

Figure 66: World Migration Patterns. Illustration from McKinsey Report, “Global Migration’s Impact and Opportunity.”[8] WW107

That said, most economic migrants not surprisingly move from poorer countries to richer ones. The table below shows the countries with the highest number of migrants and their percentage of the population.

Table 21: Top 11 Countries by In-Migrants

| Country Name | 2015 Migrant Count | 2015 % of Population |

| United States | 46,627,102 | 14.5% |

| Germany | 12,005,690 | 14.9% |

| Russian Federation | 11,643,276 | 8.1% |

| Saudi Arabia | 10,185,945 | 32.3% |

| United Arab Emirates | 8,095,126 | 88.4% |

| Canada | 7,835,502 | 21.8% |

| France | 7,784,418 | 12.1% |

| Australia | 6,763,663 | 28.2% |

| Spain | 5,852,953 | 12.7% |

| Italy | 5,788,875 | 9.6% |

| India | 5,240,960 | .4% |

| High income | 157,500,496 | 13.3% |

| Low & middle income | 84,287,737 | 1.4% |

| World | 243,192,681 | 3.3% |

Source: United Nations Population Division via World Bank Indicators Interface. Migrants in this context include all people born in a country other than the one in which they reside, so both permanent immigrants and migrant labor.

About 2/3 of international migrants settle in high income countries. Indians work in the oil rich Arab countries while Germany hosts many Eastern Europeans and more recently a flood of Syrians and Afghans. Australia’s largest group of immigrants is from England, followed by India, China, and New Zealand, while in the US the largest groups of migrants are from Latin America and Asia. India hosts a lot of migrants, but they are a tiny percent of the population, and far more Indians (17.5 million) are out-migrants. The huge population of India can lead to some confusing statistics, the 17.5 million Indians living outside the country, while the largest national group of migrants, represent a migration rate of only 1% of the Indian population.

The chances of a migrant becoming a permanent resident vary greatly between countries. In the oil rich economies of the middle east, migrants are contract workers employed directly by businesses. In the United Arab Emirates, over 90% of the workforce are migrants, in large part from India. While many migrants have been abused, there is a long-standing historical connection between the two countries and some Indian families have lived there for generations under work visas and flourished. But the UAE and Saudi Arabia limit citizenship to Arabs with specific lineages and no migrants can gain citizenship[9]. As a result, all of the migrants in Saudi Arabia and the UAE are temporary guest workers. In the US, as we have seen, anyone accepted as a permanent resident can apply for citizenship after 5 years. In Germany visa holders can apply after 8 years. The primary bar to citizenship in the US and Germany for older permanent residents is undoubtedly the language requirement. There will be somewhat different economic effects between a guest worker and an immigrant population. Immigrants become part of the country’s human capital in a way that guest workers don’t.

Economics of In-Migration

From the point of view of the receiving country, immigrants and guest workers are “in-migrants”. We saw in the case of the United States that permanent immigrants form the large bulk of in-migration accumulated over time. The US also has a guest worker program that allows for foreigners to work under temporary visas.

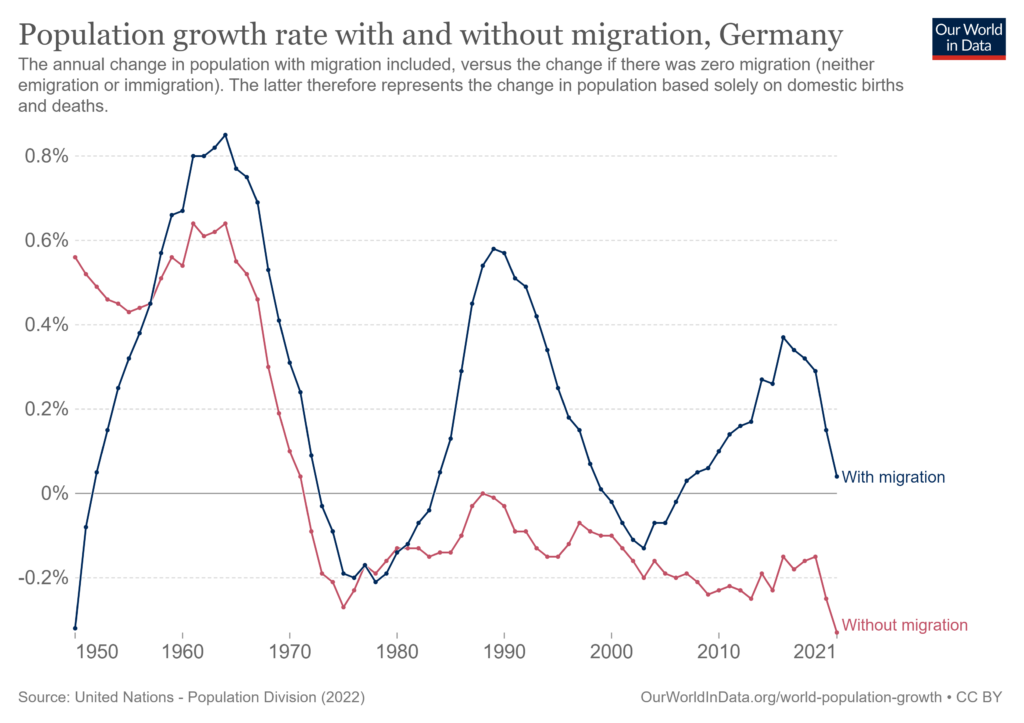

Much of what applies to immigration in the US also applies to other “advanced” economies. Worldwide, fertility rates are falling, and are below replacement levels in many richer countries. Below is the population growth – or shrinkage – in Germany with and without migration.

Figure 67: Germany hosts many refugees but has had difficulties with attracting the highly skilled workers its economy badly needs. Source: Our World in Data[10]. WW108

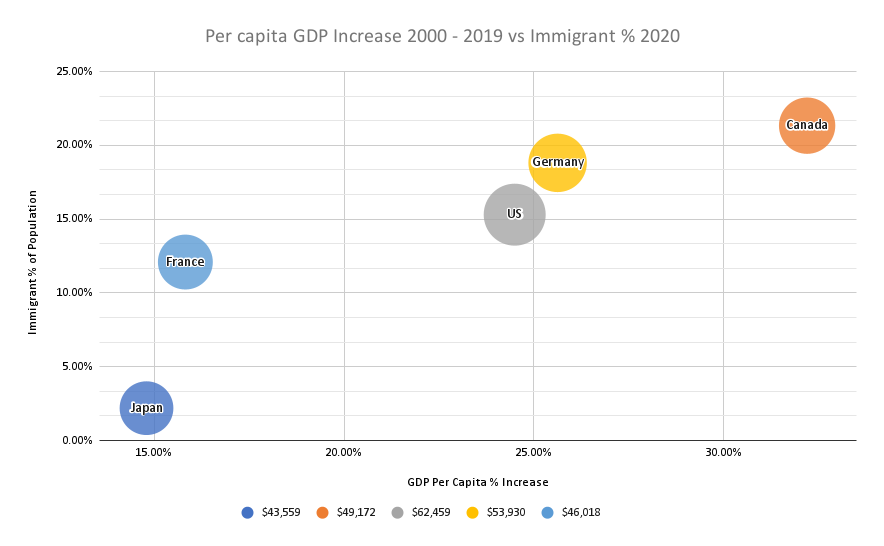

In the chart below, the immigration percentage of is plotted against GDP per capita growth for some countries with complex advanced economies.

Figure 68: Immigrant percent of the population vs real growth in per capita GDP from 2000 to 2019. The size of each bubble indicates the per capita GDP of the country. This chart does not show growth in immigrant population, rather the percentage of immigrants in 2019. Data Source: World Bank Indicator Data WW109

As in the case of US states, the clear correlation between immigrants as a percent of the population and per capita GDP increase doesn’t tell us the direction of causality, if any (they might both be correlated with some other factor or factors). An econometric study of the effects of immigration flow on growth in 22 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries found that “first there exists a positive impact of migrants’ human capital on GDP per capita, and second, a permanent increase in migration flows has a positive effect on productivity growth. However, the growth impact of immigration is small even in countries that have highly selective migration policies.”[11] In other words, even in countries that predominantly admit highly skilled immigrants, such as Canada and Australia, immigrants don’t slow down growth, but they don’t accelerate it much either as far as statisticians can tell. Of course, overall growth in GDP (a country’s total output), rather than GDP per capita, rises or falls with population growth, or decline. Japan is a country with very few immigrants and recently a falling population. Its aging demographics is considered to be one of the factors in its very slow rate of growth in both GDP and GDP per capita in recent decades.

Guest workers allow for more targeted matching between labor needs and migrant labor.

Economics of Out-Migration (Emigration and Overseas Work)

So far, we have looked at how immigration and guest workers affect the receiving country, but in-migration is only half the story. Every migrant comes from another country, what is the effect on those sending countries of out-migration?

Economic migrants mostly leave poorer countries to work, study, or permanently live in richer ones. In some countries, such as the oil rich UAE and Saudi Arabia, permanent residency and citizenship aren’t options, migrants usually go to these countries to work, save, and send home remittances. In advanced economy countries such as the United States there are both “guest workers” and permanent immigrants admitted, and both groups send home remittances. Worldwide remittances totaled $657 billion in 2019 which dwarfs official development assistance of $168 billion[12]. Of course, this flood of remittances helps boost economies in the migrants’ home countries, and since it flows directly is not subject to the corruption that often plagues official assistance.

So, are emigration and overseas work on balance good for the migrant’s home country? Does migration speed economic development? How does it affect wages and employment? As usual, different studies provide a range of results, partly because they study migrant populations from different countries or regions. Keeping that in mind, here are some of the findings.

Economic migration doesn’t have much effect on the overall employment rate in the sending country. Most migrants have jobs before they leave, and these jobs do not go empty after they leave, even in countries with relatively low unemployment such as the Philippines. If overseas workers are included, overall employment increases. However, a lot depends on the “replaceability” of the skill the migrant takes with them, the famous “brain drain”, discussed more below[13].

Employment may not change much in the sending country, but studies have found a positive effect on wages[14]. While it might seem that higher wages would drive down labor demand and thus lead to higher unemployment, we have to remember that repatriated wages are also driving up demand in the migrant-sending country. The rise in wages and increased demand encourages further capital investment[15].

While most migrants are not extensively educated, a sizable portion are. “Brain drain” happens when highly educated people migrate and take with them their native country’s investment in their education. It’s not just about money, many talented students from less developed countries go to school in advanced countries and end up staying there, depriving their native country of their human capital. However, there can also be positive effects from highly educated people emigrating for better wages. In addition to their substantial repatriations, the very promise of higher pay overseas can encourage students to seek higher education in their own country, and if enough of them stay, this can have a positive effect. In the Philippines, as doctors and nurses left for the US in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the number of medical and nursing schools ballooned. While many graduates emigrated (and sent home a substantial regular flow of money), enough stayed to increase the supply of doctors and nurses at home[16]. It is also true that emigres sometimes return, bringing their accumulated education and experience back with them, usually when there are increased opportunities in their native country. To quote one source:

“[Brain drain] can be a boon or a curse for developing countries, depending on the country’s characteristics and policy objectives. … effective brain drain exceeds the income maximizing level in the vast majority of developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa,

Central America, and small countries.”[17] In other words “brain drain” hurts most developing countries, especially the smaller ones.

The overall picture on the effect of emigration and overseas work on development varies from country to country. On the one hand, repatriated wages help spur demand and growth in the sending country, and substantially increase the income of the migrant families back home, but on the other hand the migration of highly skilled and educated workers can negatively impact development. Some countries have pursued successful development programs with hardly any overseas migration and vice versa. It is in fact development that tends to determine the extent of migration rather than the other way around, and there is no substitute for the conditions that lead to growth. As we saw in the section on Developing Countries Productivity & Convergence these include stable government, a suitable legal and regulatory environment, an educated workforce, less corruption, as well as natural factors such as country size and resource base.

[1] https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ accessed March 3, 2023

[2] https://www.unhcr.org/ukraine-emergency.html accessed March 3, 2023

[3] The earthquakes of early 2023 didn’t help the situation.

[4] UNHCR – Refugee Statistics accessed Mar 30, 2023

[5] https://data.unhcr.org/en/news/11128

[6] Refugee Camps | Definition, facts and statistics (unrefugees.org)

[7] UNHCR – Refugee Statistics accessed Mar 30, 2023

[8] Woetzel, Jonathan, Anu Madgavkar, Khaled Rifai, Frank Mattern, Jacques Bughin, James Manyika, Tarek Elmasry, Amadeo di Lodovico, and Ashwin Hasyagar. 2016. “Global Migration’s Impact and Opportunity.” McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/global-migrations-impact-and-opportunity#/.

[9] Early in 2023 Saudi Arabia announced plans to allow children of mixed marriages to apply for citizenship.

[10] Hockenos, Paul. 2023. “Skilled Migrants Aren’t Interested in Germany.” March 22, 2023. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/22/skilled-migrants-arent-interested-in-germany/?utm_source=PostUp&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Editors%20Picks%20OC&utm_term=75904&tpcc=Editors%20Picks%20OC.

[11] Boubtane, Ekrame, Jean-Christophe Dumont, and Christophe Rault. 2015. “Immigration and Economic Growth in the OECD Countries 1986-2006.” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2622005.

[12] Our World in data https://ourworldindata.org/migration

[13] Asch, Beth J., and Courtland Reichmann. 1994. Emigration and Its Effects on the Sending Country. Rand. pages 31-32

[14] IBID pages 32-33

[15] IBID page 33, study of Pakistani construction workers

[16] IBID p 73

[17] Docquier, Frédéric, and IRES (UCLouvain), Belgium. 2014. “The Brain Drain from Developing Countries.” IZA World of Labor: Evidence-Based Policy Making. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.31.